Big, fat failure is the key to realizing your dreams. The funny thing is you already know failure is good for you.

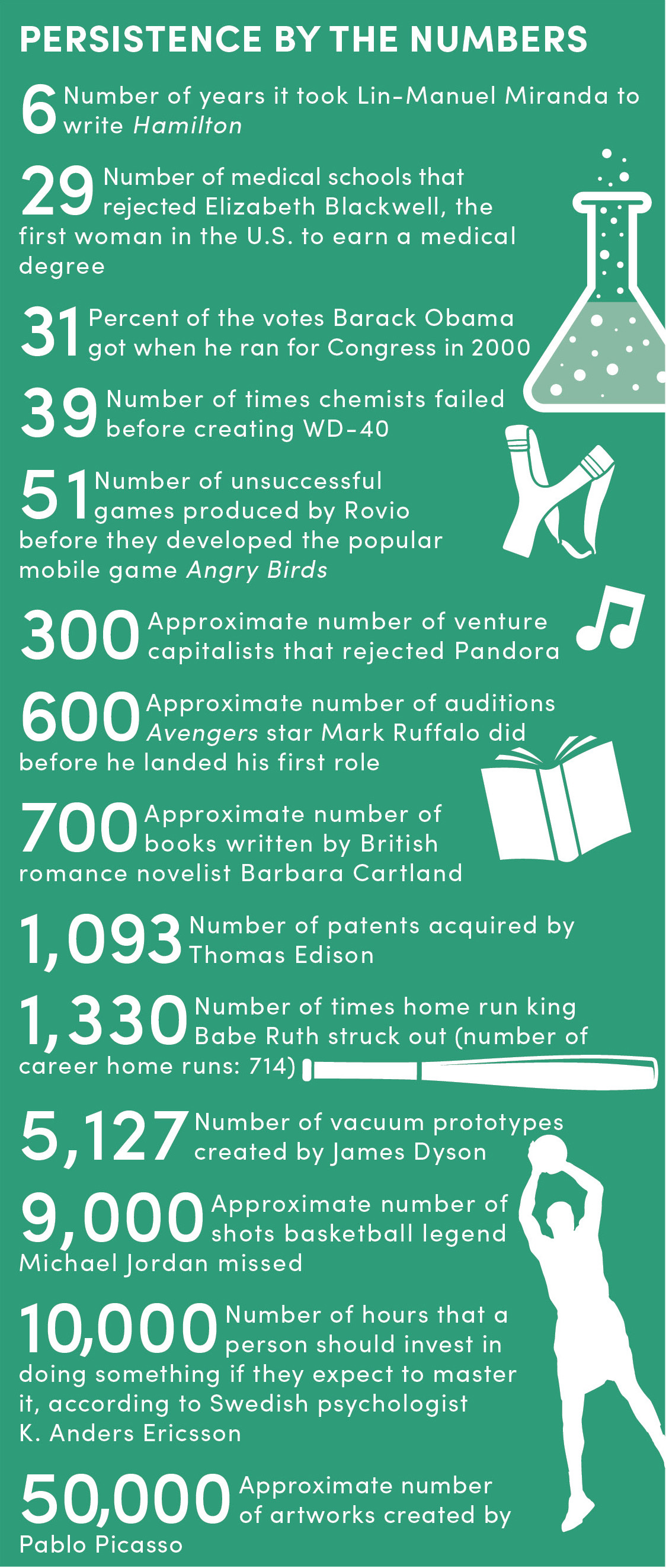

We hear about failure all the time: Actors who were rejected at hundreds of auditions (until they weren’t), entrepreneurs whose first dozen ideas were garbage (though their next one was brilliant), and inventors with strings of useless inventions (and some that changed the world).

Details and statistics like these make us feel good, but they boil down to an uncomfortable question. If failure is the key to getting what we want, why do we do everything in our power to avoid it?

In Guy Winch’s book Emotional First Aid: Healing Rejection, Guilt, Failure, and Other Everyday Hurts, he explains: Rejections are painful, and for a good reason—during our prehistoric past, we were only as strong as our social groups. “Being ostracized would have been akin to receiving a death sentence,” Winch writes. To save us from dying alone in the wilderness, our brains evolved a clever trick—a pain-trigger—to teach us to do everything possible to avoid rejection. We’re here today because our ancestors avoided rejection at all costs.

Fast-forward a few thousand years. You’re still reinforcing those anti-rejection cues, and in fact, you’ve been doing it for as long as you’ve been alive. You remain snugly in your comfort zone because your feelings tell you to, and it’s your feelings that you have to overcome if you want to take that risk, launch that idea or send that proposal. You won’t do what feels hard. If you’re planning to put yourself out there only when you feel like it, you’ll be waiting forever. In fact, there’s probably something right now that you’re avoiding. And that might be the thing you have to push yourself to do—whether you feel like it or not.

Our brains dose us with a feel-good chemical, dopamine, when we do something right. The dopamine level drops when we do something wrong. In her book, The Up Side of Down: Why Failing Well Is the Key to Success, Megan McArdle explains that we gain skills by practicing things because we’re strengthening the connection between the action and the reward. When we’re expecting an action to elicit a certain response and it doesn’t, our dopamine levels drop, and the connection fades. “Failure feels bad precisely because it’s the way your brain says, ‘Hey, don’t do that anymore,’ ” McArdle writes. But if we learn from the failure and revise our actions, we might get a better result (and a dose of dopamine) on the next try.

And that next try? It’ll actually be easier. Psychologists use a tactic called exposure therapy, which is the process of gradually introducing phobic people to things they avoid. It might be heights or spiders or snakes. Or it might be the fear of putting yourself out there to fail. Every time you do that scary thing, you get a little more acclimated, and it becomes a little easier. In a 2014 LinkedIn article, Steli Efti, CEO of Close.io, described his experience in helping an employee overcome his fear of cold-calling—which was, more specifically, a fear of rejection. Efti instructed the employee to fail miserably for the whole day. As per those instructions, the employee was rejected all day, call after call. And somehow, it cured his fear. He realized the failure he’d feared wasn’t actually so bad, and he didn’t worry about it anymore. He learned.

And that’s what the process of failing is, at its core: a simple learning experience. In Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Carol Dweck, Ph.D., explains what happened when she gave a group of children increasingly hard puzzles to solve. As the puzzles became more difficult, the children became more excited. They were actually pleased by the challenges. Baffled, Dweck concluded: “Not only weren’t they discouraged by failure, they didn’t even think they were failing. They thought they were learning.”

Aim to be like those kids. Remind yourself that messing up is the best way to learn—the best way to figure out how to do things better, what to do in the future, and how to avoid the pitfalls that snagged you the first (or second or third) time around. If you’re learning a second language, you’re going to sound like an idiot before you’re fluent. If you’re trying to grow tomatoes, there will be a few plant casualties before you get a great harvest. If you’re writing a book, there will be parts you have to revise or completely rewrite.

“Failure is an essential part of moving forward, of learning, of being human.”

It’s true that your inclination to melt into your couch instead of putting yourself out there for failure is the result of millions of years of evolution. It’s true that your instincts want to save you from unnecessary emotional pain and general awkwardness. But failure is an essential part of moving forward, of learning, of being human. And with a little understanding, some exposure therapy, and a few solid tips, you can beat your feelings and be on your way to failing (and succeeding)—awesomely.

Try Rejection Theraphy!

Rejection is that much-dreaded response that hits us right in the self-esteem. It’s the worst, and it’s no wonder we’re programmed to avoid it at all costs.

Which makes a game like Rejection Therapy seem practically impossible—at least at first. In Rejection Therapy, rejection is the only way to win. And in fact, it’s the only real rule: You must be rejected. Once a day, every day, another person must turn you down or deny your request. Ask for a discount before you purchase something. Request an item at a restaurant that’s not on the menu. Strike up a conversation with a complete stranger. Ask for goods, favors or services until someone tells you no.

If you’re getting anxious just thinking about this, you’re not alone. That’s exactly why Jason Comely developed the game in the first place—to help himself (and ultimately, people around the world) overcome the fear of rejection.

Comely was raised in Canada, where he shoveled sidewalks in the winter and sold doughnuts door-to-door in the summer. He was an artistic type and never very good with money. When his wife divorced him, he left a grueling factory job and moved to a new town to make a new start. His fledgling website design and consulting business kept him busy, but he was often alone and isolated. Even when he tried to socialize, he was filled with crippling anxiety and would quickly retreat to his comfort zone—his lonely apartment. One Friday evening, he was puzzling away, trying to understand his own mind.

“It just seemed so unfair that some people could be so social and I had so much trouble,” Comely says. “Then it hit me: I was afraid of rejection. My narrative was that I’m a trailblazer and I’m independent and I don’t care what people think. It wasn’t the truth.”

He realized that he had to change his mentality and push outside his comfort zone. And the only way to do that would be to force himself to face his fear. He reasoned that if he became familiar with rejection and social failure, he might not fear it as much. So Comely vowed to be rejected every single day.

At first it was unbearable. But after a few abortive attempts—including a near-breakdown in a bookstore—Comely received his first rejection. With a dry mouth and sweat forming at his temples, he approached an attractive woman on the street and nervously asked her for directions. She brushed him off. It was a small step, but Comely was elated. The first barrier was broken.

“I felt like the rules didn’t count anymore, like I could ask whatever I wanted,” Comely says. “I was giving myself permission to fail.”

As he began to experiment, he felt as though he’d discovered a secret. Soon, he’d rewired his thoughts: Comely had trained himself to go for it—to ask for things, to try new things, to not worry about the outcome. Anything became possible because he no longer feared the worst-case scenario—a rejection. He was disobeying his fears, and it had opened the world to him.

On his website, (RejectionTherapy.com) Comely sells cue cards with ideas on ways to be rejected: Request a lower interest rate from a credit card provider; challenge a stranger to an arm-wrestling match. As long as you’re rejected, you’re winning the game. And plenty of people have won: Comely says he receives letters from people who were previously trapped by their fears, people who were afraid to leave their comfort zones. Now they attribute their marriages, new jobs and educational opportunities to Rejection Therapy.

“Fear has so many different disguises and they are all the ways we fool ourselves into staying in our comfort zone,” Comely says. “The underlying philosophy of Rejection Therapy is sort of Zen: It’s about not being attached to the outcome. To stop overthinking. To redefine rejection as positive, because you did it—you opened the door. That’s the important thing.”

Failure 101: What You Should Know About Flopping

- Get out of your head: Anytime you find yourself overthinking something, you are stalling. It’s a cue that you need to act.

- Baby steps: Don’t start with the big stuff, you are in training. Pick something small, take a calculated risk and get ready for a few minor failures.

- Play the numbers game: All you need is the right person to take an interest. Keep putting your ideas out there until you find the one who says yes.

- Desensitize yourself: The more often you put yourself out there, the more accustomed you’ll become to failing—and it’ll be easier each time. Try to fail at something once a day.

- Act without permission: Stop waiting for the establishment to pick you; find ways to get your ideas out there on your own. It won’t always work, but it’s always worth a shot.

- The Five-Second Rule: When you have an impulse to act, you must move on it in five seconds, or your brain will kill it. Make it a habit to act.

- Be yourself: Listen to your instincts and blaze your own trail to victory (and failure). Get inspired by others, but remember your path and your failures are yours.

- Plan to fail: Yes, you’re going to fail—many, many times. So what! Push yourself to do it anyway so that your feelings don’t stop you. You might just surprise yourself and succeed.

Afraid Of the Unknown? You’ll Figure It Out

From Mel Robbins’ book, The 5 Second Rule:

I had a conversation with my 15-year-old daughter last winter that illustrates just how debilitating all of this thinking and feeling actually is.

To give you some background, Kendall is a very talented singer and dreams of pursuing music as a career. From the moment she wakes up until the moment she goes to bed, she’s singing. She has been involved in community theater and school musicals since elementary school and now she lives and dies for her high school a capella group.

Recently, one of her mentors recommended her for an audition with the directors of a musical in New York City. He had directed Kendall in a community theater program for years and had placed kids on tour with Les Miserables, Mary Poppins and Matilda. He thought she had a good chance.

The second the topic came up, she said she wanted to but hesitated for weeks on writing her mentor back about it. We were away for Christmas break, and during a walk on the beach, I asked her why. It was fascinating and heartbreaking to hear how her thoughts and feelings had trapped her.

Funny enough, she wasn’t afraid of the audition itself. At least not when she thought about it. It was everything that might happen after the audition.

First, she was afraid her friends would judge her for even trying out. She believed that if her friends heard she had been invited to audition, they would judge her for “thinking I’m better than them, ya know? I mean, who am I to think that I could ever be in a musical on Broadway?”

Then she was worried she might actually get the role. And if she did, how much would her life change? Kendall detailed the questions she’d have if she succeeded: Would she have to move? Where would she live? What would it be like to go on tour? What would her friends think? Would she even have any friends?

The what-ifs went on and on. (We call this the “What-If Loop”—whenever you’re stuck in it, just say aloud: “I’ll figure it out” and then push yourself forward. It’s the thinking that paralyzes you; the action forward will free you.) And of course, Kendall had all the associated fears you’d expect with facing the unknown. She wondered and worried about what it would look like if she actually got what she wanted.

I hate when people say they’re afraid of success. It’s just not true. You want it. You just don’t want the uncertainty that comes when you think about a new life. And all that overthinking is just a habit—it’s triggered by the feeling of uncertainty. Like Kendall, you’ll figure it out. She wants the role, don’t kid yourself—she just wants it free from judgment and uncertainty.

But that fear of judgment wasn’t the end of our conversation. There was a second reason she hesitated: the fear of sucking. She said that she didn’t want to try out because: “What if I didn’t make it, Mom? What if I am not as good as I think I am? If I don’t audition, at least I can tell myself that I’m amazing—I’m just too lazy to have what I want.”

Now we were getting somewhere. The fear of sucking, not being good enough, feeling like a loser—none of us wants to face that reality. So we avoid it like the plague. We dodge challenges to protect our egos—even if it means eliminating the possibility of getting what we want.

I listened to Kendall talk about her fear that she wasn’t good enough, and then asked her one simple question: “What if you’re wrong?”

If success is a numbers game (the more times you try, the more likely you’ll succeed) and confidence is a muscle you build (the more times you try, the more confident you become) and failure is the way forward (the more times you try, the more you learn), then the key to life is learning how to beat the feelings that stop you. The steps, the advice and the actions are simple. Your feelings about doing the work are the problem. It’s time to ignore what’s in your head and push yourself forward when feelings of doubt and fear try to stop you.

Your Heroes Are Failures Too

Famous Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh had a slew of unsuccessful stints before ever picking up a paintbrush, including being fired from a job as an art dealer and pushed out of preaching by his sponsoring church. He only sold one painting in his lifetime.

Oprah Winfrey, media mogul and talk show host with a net worth of $3 billion, struggled early in her career: She was kicked off the anchor chair at WJZ-TV in Baltimore after just a few months.

After dropping out of college, pop star Madonna took a job at Dunkin’ Donuts—only to be fired for spilling jelly on a customer.

Henry Ford was known for founding Ford Motor Co., but his first company, Detroit Automobile Co., was a short-lived flop.

Before I Love Lucy, Lucille Ball’s drama instructor told her to find another profession.

Before they co-founded Microsoft, Bill Gates and Paul Allen started Traf-O-Data, a sometimes-faulty device you’ve never heard of for a reason.

For Katy Perry, who’s sold more than 83 million digital singles and 6 million albums in the U.S. alone, it’s been a long road to fame: Her first album was a failure and she was dropped by Columbia Records.

Decca Records rejected The Beatles in 1962, telling them that guitar groups were on the way out.

It took the Wright Brothers almost six years of failed attempts and prototype-tweaking before they perfected their design for the first practical airplane.

After auditioning to sing at a club in 1954, Elvis Presley, the King of Rock ’n’ Roll, was told to stick with truck driving—because he’d never make it as a singer.

If you’re invigorated with creative energy and filled with a drive to get out there and do something, don’t let it go to waste. Remember, if you don’t act on an idea right away, you risk losing it forever. Here are a few tips to get you on the path to failing awesomely:

Practice Rejection Therapy: Confront the thoughts, fears or feelings that are holding you back until they no longer scare you.

What’s one area of your business or life in which you notice yourself holding back? Practice Rejection Therapy: Confront the thoughts, fears or feelings that are holding you back until they no longer scare you.

How can you begin making smaller moves toward your goal? Break down big steps into little ones so that you can try (and fail) more often.

Have you experienced failure or rejection recently? If so, start the learning process now: Think about why you failed and jot down what you can do to get a better result next time.

This article originally appeared in the August 2016 issue of SUCCESS magazine and was published in July 2016. It has since been updated. Photo by GaudiLab/Shutterstock