The home team is in vivid yellow—except for the pitcher, whose pants are around his ankles. The batter is trying to ignore the Fruit of the Loom underpants on the mound, but the infielder krumping at second base is no less intimidating. The packed house at Grayson Stadium in Savannah, Georgia, has no idea what will happen next.

The players aren’t the only ones off-kilter here (though some of them are wearing kilts). The team’s cheerleading squad, the Man-Nanas, is composed of men with dad bods. The dance troupe, the Banana Nanas, is designed for grooving grandmas over the age of 65. The umpire’s third strike call is to spontaneously start flossing, dougie-ing or powering down like a robot. The whole ballpark smells like a banana cream soda.

I’d say this is a normal evening of Banana Ball, but “normal” is a risky word to use around the Savannah Bananas.

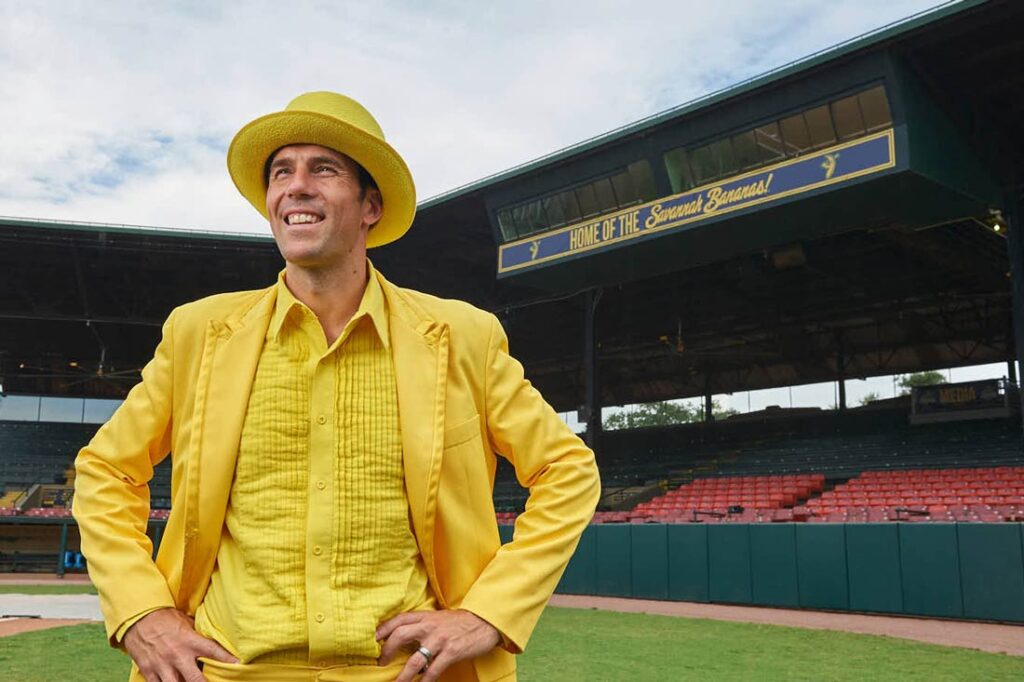

The head of the bunch is Jesse Cole. He’s the club’s owner and founder, but you won’t find him sitting in the owner’s suite. As a matter of fact, Cole’s rarely sitting at all. He’s boogying in the dugout and belting out Bon Jovi with fans in the bleachers, all while reliably besuited in his iconic yellow tuxedo. His ringmaster antics have earned him the nickname “the P. T. Barnum of Baseball,” a moniker that fits insofar as Cole is both a master entertainer and a shrewd businessman. The Savannah Bananas’ axiom? “Fans first. Entertain always.”

Putting Savannah Bananas fans first

Those four words have been the Bananas’ guiding star since 2016. Cole’s strategy for living out the “fans first” mission is to assess what’s normal in baseball and do the opposite. Literally.

Normal stadiums are plastered with advertisements, so Grayson Stadium has zero. At normal ballparks, tickets and concessions are separate purchases. At Grayson Stadium, food and drink comes with your $25 open-seating ticket. And that’s a flat price, because the Bananas cover all the fans’ taxes on tickets, merchandise and convenience fees.

“It’s astronomical, the money we leave on the table,” Cole says. “I think you can look at any sports team or any business [and ask,] ‘Where is the money coming from?’ and then that’s who the organization works for; 99% of our revenue comes directly from our fans.”

Naturally, the Bananas’ measurement of success is drastically unlike an orthodox sports team’s. The key performance indicator isn’t a healthy win-loss ratio or a glimmering trophy cabinet—it’s whether the fans come, stay and come back. And between an ongoing streak of sold-out home games since 2017, a waitlist of around half a million fans and over 5 million more TikTok followers than the Yankees, it’s obvious the world has gone Bananas—and that’s all the Bananas have ever wanted.

“I don’t want to be a billion-dollar company. I want to be a billion-fan company,” Cole says. “If you create a billion fans, everything else will take care of itself.”

Keeping the faith when things look grim

To put fans first, first you need fans. A truism, sure, but this was the valley of death Jesse Cole and his wife Emily had to cross when they bought a dinky expansion team in Savannah, Georgia, eight years ago. When the Coles arrived at their new stadium in October 2015, it was completely deserted, the phone and internet lines cut, the stadium stripped bare. Although the couple was optimistic they could break the trend, three months of truly meager ticket sales (according to podcast episodes featuring Cole, they only sold two tickets) seemed to prove their investment was dead on arrival.

“On Jan. 15, specifically on Friday at 4:45 p.m., I got a phone call that we’d overdrafted our account and the team was out of money,” Cole says. “So, we sold our house. We emptied out our savings account. We got a dump down in Savannah.”

The Coles’ Savannah-or-bust venture was quickly trending toward the latter. Their initial energy was waning from sleepless nights on a cheap air mattress. They budgeted $30 per week for groceries, which comes out to spending around $1 per meal, per person—assuming you skip breakfast.

“We had nothing,” Cole says. “But we still believed in what we were doing.”

Savannah Bananas’ on-field antics

With nothing left to lose, Cole threw caution to the wind. The team was reskinned and became the Savannah Bananas. Their first game was the debut of the Banana Nanas (the senior citizen dance team), a breakdancing first-base coach and the official Banana Baby. Cole showed up dressed like a yellow Mad Hatter.

The game sold out.

“We actually made six errors. We played terrible,” Cole says. “But we started selling out every game [after that].”

And they haven’t looked back since. The 2016 season even saw the Savannah Bananas crowned “2016 [Coastal Plain League] Organization of the Year.” But despite the success, Cole still noticed fans leaving games early. By 2017, even he was bored during the game.

“So I looked at every single thing in baseball that was too long, too slow, too boring and said, ‘Could we do the opposite?’” Cole says.

Playing by new rules

The first game of Banana Ball was an exhibition game played in 2018 in just 99 minutes. It’s a recognizable form of baseball (for now), but it has evolved to accelerate the game, involve the fans and inspire as much drama as possible. For instance, there’s a strict two-hour time limit. Hitters aren’t allowed to step out of the box on penalty of strike, and bunting is prohibited on penalty of ejection. If a fan catches a foul ball, that’s an out. In the event of a tie after two hours, a “showdown tiebreaker” begins.

Perhaps the most radical change of Banana Ball is that walks have been replaced with sprints. On ball four, the runner breaks into a mad dash around the bases while the defense launches into a rapid-fire game of catch. All defensive players are required to touch the ball before they can try to tag the runner. If it’s timed just right, they’ll punch him out by the time he reaches second.

If you’re an old-school baseball fan, this might all sound silly to you. But the Bananas and their fanbase are serious about the new take on an old sport. In August 2022, the Savannah Bananas announced they would be leaving the Coastal Plain League and exclusively playing Banana Ball from now on.

Creating a nemesis for the Savannah Bananas

Banana Ball’s breakneck pace and the players’ in-game hijinks have drawn comparisons to the legacy of the Harlem Globetrotters. Indeed, just like the Globetrotters concocted the Washington Generals to be a convenient nemesis, the Bananas have created the Party Animals, who wear sleeveless jerseys and whose logo is (of course) a monkey wearing a banana peel on its head like a hat.

But while Globetrotters-Generals games were scripted, the Bananas-Party Animals rivalry preserves authentic athletic competition. The shenanigans are rehearsed but the game itself isn’t predetermined, which only adds an unknown to the organized chaos of it all. Teams still play to win—this season, in fact, the Bananas are scheduled to play 22 games of Banana Ball against external opponents.

“I am obsessed with how to bring in the competitiveness and the stakes to what we’re doing,” Cole says. “Banana Ball is a game for the 21st century, a game that’s fast, that’s highlight-driven…. [There are] big stakes for Banana Ball as we build the legitimacy of the game in addition to the Bananas show.”

Refusing to play it safe

Of course, it’s natural for the Bananas to slip on their own peels. When asked about stunts that have failed, Cole just laughs.

“I get asked that question in probably every interview,” he says. “My mind doesn’t work like that. I’m just so focused on the next at-bat that I don’t process or think about [failure] too much, because then it will keep you from trying new things.”

You can probably imagine the endings to stories about an all-day beer festival, a bagpiper halftime show or something called “the Living Piñata.” But as Cole says, if you’re not getting criticized, you’re playing it too safe. And with the team’s world tour schedule expanding each year, fresh ideas are what keep the Bananas from getting overripe.

“I believe we work our idea muscle [more than] any sports and entertainment brand there is,” Cole says. “Every night we bring 10 to 15 things to the field that we’ve never done in front of a live crowd.”

Living up to the Savannah Bananas’ axiom: ‘Fans first. Entertain always.’

He adds that remaining new is a way of life for the Bananas, which can be translated to mean, “by staying new, we’re putting fans first.” Every night, fans see something they’ve never seen before. The mission is that every fan can experience an “I-was-there-when” moment. When you cultivate a culture where nothing can be predicted except a good time, the risk of normalcy (or as Cole puts it, boredom) disappears.

The fans are eating up the new national pastime. Women call in the day they find out they’re pregnant, just to enter their baby on the waitlist to be the Banana Baby. Even major league teams are taking notice, inviting the Bananas to grace their stadiums.

And while Cole is fanatic about the present-day fanbase, his eyes are still peeled for that billionth fan.

“We’re just in the first inning.”

This article originally appeared in the May/June 2023 issue of SUCCESS magazine. Photo by ©Malcolm Tully.