Join Peter Diamandis for a free webinar that teaches the eight steps for Exponential Thinking on Jan. 17 and discover what you can accomplish.

It is a museum to wild optimism in action.

Hallway exhibits at the offices of the XPRIZE Foundation celebrate the advances the prizes have spurred. Grants have been awarded to the first privately funded space flight, revolutionary oceanic oil spill cleaners and ultra-efficient automotive engines, among others. It’s now chasing huge gains that include education apps, ocean floor mapping, robotic moon exploration—world-class breakthroughs, the stuff of sixth-grade “what I want to be when I grow up” essays. These competitions, open to any and all comers, reward the egalitarian idea that if you bring enough ingenuity to a problem, people will eventually make the impossible seem ordinary. Here’s a nugget written on one whiteboard in the office: “Labor omnia vincit.” Work conquers all. You don’t have to believe it to appreciate its buoyancy.

Related: Xponential Advantage: Hacking Your Mindset to Get What You Want

The headquarters is in Culver City, California, in one of those sleek, anonymous glass boxes that dot the Sun Belt, a short ride from Los Angeles International Airport. This is where you’ll find Peter Diamandis on a bright spring afternoon. When he’s at his desk, which is almost never, the nonprofit’s CEO and chairman overlooks a highway and what appears to be a film studio storage space, where dreams go to sit in a parking lot. On the day a photo crew visits for a shoot, a photographer perches him on a low wall in the office lobby, where a mural of space from an astronaut’s perspective gives him a view of the Earth’s blue curve. Overhead hangs a car-sized model of SpaceShipOne, the craft that captured the first XPRIZE.

Say this for Diamandis: He’s pretty much up for anything. He shimmies out toward the stars and obliges with a couple of thumbs up, looking like a guy who just won the world in a raffle. “It’s a good planet here,” he jokes. Later someone walks past him as he poses outside the building and razzes him: “Blue Steel, Peter, Blue Steel!” He takes the rest of the air out of his own tires. “This and five bucks will get you a cup of coffee,” he calls back.

By all appearances, Diamandis is robust for a man of 55. He’s compact and trim, with wide shoulders and angular features, and a glint of silver at the edges of his hair. Yet to hear him describe the next venture looming on his horizon, a diagnostic and therapeutic company in San Diego called Human Longevity Inc., you realize he’s obsessed with overturning the very idea of aging, of health care, and possibly of death itself.

If he’s successful, your grandkids will be nearly twice his age when they start to go gray. Human Longevity Inc. (HLI, for short) is shooting to make 100 the new 60, he likes to say. By that metric, it seems 55 becomes the new 30-something.

Is it really that unreasonable, considering the nature of medical advancements and human progress, to think any of us could live to 150? Diamandis is actually shooting much higher.

“I’m just hitting the first third of my life. It changes your perspective on what you’re able to do, willing to do.”

“I’m just hitting the first third of my life. It changes your perspective on what you’re able to do, willing to do,” he says. “When I was in medical school, 30 years back, I remember reading about species on this planet that lived hundreds of years—large whales, sea turtles, lobsters. It was like, If they can, why can’t we?

JEFF KATZ

JEFF KATZ

“And I set a ridiculous number. I set a target of a 700-year lifespan. It was ridiculous only because if you can live that long, you can live forever.”

You might have identified a different reason why Diamandis living 700 years would seem ridiculous. But that’s where you, and pretty much everyone who has ever lived, differ from Diamandis. The entrepreneur, engineer, M.D. and futurist has made a career of thinking across decades, potentially centuries. When he makes pronouncements such as the one he gave at the International Space Development Conference in 2006, that asteroids packed with precious metals represent world-changing troves—“There are $20 trillion checks up there waiting to be cashed”—he isn’t talking about technology on the timescale of, say, the iPhone 9. He’s looking deeper in the 21st century and possibly beyond. Now he’s just got to get that far.

His living philosophy goes by the shorthand “abundance thinking,” a certain style of future-focused appraisal that looks for opportunities in the general bend of history’s long arc. Forget election shenanigans, riots, stock dips, train derailments. Viewed across enough time, the thinking goes, humans find ways to maximize resources, to solve intractable problems, to avoid wars, to democratize information, and generally to get more out of life. To that end, Diamandis has lived this sort of applied optimism. He scooped up degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in molecular genetics and aerospace engineering before going to medical school at Harvard and launching a series of ventures that are unabashedly aspirational. Diamandis co-founded Planetary Resources, a company that is building nimble spacecraft to explore and assess asteroids for mining. With futurist Ray Kurzweil, he started Singularity University, a Silicon Valley institution focused on teaching executives about the ways people and machines will interact—and potentially merge—in the coming decades. While still at MIT, he laid the groundwork to launch International Space University, an institution that found a permanent home outside Strasbourg, France.

Related: 7 Tips for Developing Your Personal Philosophy

Naturally, then, it’s Diamandis who, along with world-class experts on stem cells and gene sequencing, would launch a venture to extend human lives beyond all known physiological limits. Diamandis’s latest foray isn’t merely a business opportunity—though it most certainly is that; he figures people over 65 are sitting on $60 trillion or more in wealth. “There’s nothing people would pay more for than another 30 healthy years of life,” he says. It’s also an outgrowth of the belief that someone, somewhere, is bound to undertake such a venture just as a matter of historical course. Why not him, then? “It’s a really crazy frontier ahead,” he says.

For one, he thinks it can be done, and he can command the expertise and resources. For another: He’s going to need the extra years to see how his many predictions and projects, with their ambitious scopes, actually turn out. Yes, it seems far-fetched that he wants—even expects—the coming generations to routinely live into their hundreds, plural. But that is, in its way, no less outlandish than the wider gains that have occurred in recent history. Since 1900 the life expectancy of an average human on planet Earth has more than doubled, to nearly 80 years. That works out to hundreds of billions of years people alive today will enjoy what their great-grandparents couldn’t.

The gains being made by HLI are still well out of reach for the average American. But give it, yes, more time. For now, it’ll run you $25,000 to get the suite of services HLI offers in what it calls its health nucleus: sequencing your genome, an analysis of some 2,400 chemicals in your bloodstream, MRIs of your body and brain, and generally quantifying every useful metric of your body, your sleep, your walk, your cognition. This fully digitized version of you winds up being about 150 gigs, or six Blu-ray discs. The result is a Google Maps for your earthly being. From that level of detail, you and your doctors can customize your medical plan down to the tiny increments.

“Health care in the world today is reactive, it’s generalized, it’s not for you,” Diamandis says. “It’s for the general public who has roughly the same age or background, and it’s expensive. I see this as how we’re going to reinvent medicine.” He adds: “It will become predictive and preventive.”

The metaphor he uses is, of course, with technology. He owns a couple of Teslas—a Model X and a Model S. They’re packed with sensors. Recently the company called to tell him a technician would visit to change a particular battery that was low, something the service center’s network knew long before he was aware of it. “The same thing should exist for us as humans,” he says.

What’s more, he wants the technology to become as widely available as air travel is today. Which, not too long ago, would’ve been a ridiculous forecast. If he winds up being correct, the advances headed our way are likely to change the way we work, the way we raise families, the way we regard ourselves as humans. How would you view a marriage at 20 if you thought you’d live to 200? How would you invest if your goal was to wait until your 120s to retire? Or how would you change the way you run your business if you thought you’d be ready to cash out around age 100 or so and then have another healthy century waiting for you, just to chill?

***

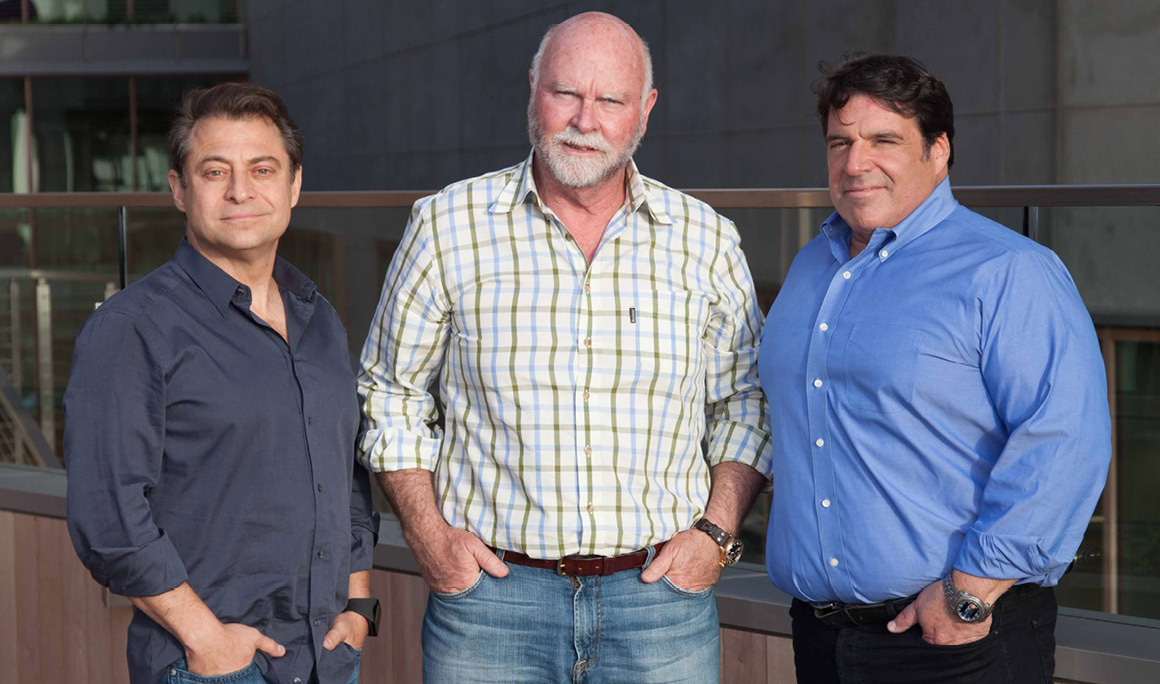

The mind-blowing part about this scenario is that many of the technologies it requires are still within the domain of speculation. Already, though, HLI is, in the words of co-founder Bob Hariri, “the largest gene-sequencing operation on the planet.” You can go there to have your 3.2 billion units of DNA mapped out, and once you do, it’ll go into a databank that Hariri, Diamandis and fellow co-founder Craig Venter hope over time will become one of the most advantageous places in the world for that data to reside. Science is still in the early phases of reading this so-called biological software we’re all running, after all. Venter was the first person to map a human genome—his own—in a project that required 10 years and $100 million to accomplish. Now, a decade after that feat, you can get your own genome mapped for a cool thousand bucks. Give it another few years, and it’ll be as unremarkable as an MRI is today.

JEFF KATZ

JEFF KATZ

The question then becomes what this constellation of billions of data points tell us. Which ones, seen in tandem, predict whether you’ll develop Alzheimer’s? Which ones, working in concert, determine your risk for coronaries and strokes and osteoporosis? To understand that, you’d have to look across thousands, perhaps millions, of people’s sequences. Which is why, as HLI gathers more and more patients’ genomes, it’s relying on a 30-person machine learning team in Mountain View, California, headed by a former Google Translate creator, Franz Och, to sift through the correlations—a process Diamandis says parallels the artificial intelligence that has made online translation increasingly reliable. As that system gets smarter, and as more people upload their genes, we’ll know even more about the future than our genes can predict.

“As you can probably imagine, an undertaking like this requires assembling a world-class team of people with diverse expertise,” Hariri says. “It requires a big vision and a willingness to set unachievable goals and chase them. One of Peter’s greatest strengths—and I say this as someone who’s like a brother to me—Peter doesn’t believe that can’t or no is an acceptable part of the vocabulary.”

Related: 5 Qualities You Need to Reach Your Biggest Goals

For now, though, there is a lot of can’t. But treating the unknown is where Hariri’s expertise comes in. He’s one of the world’s top experts in stem cells, the infinitely malleable, endlessly useful cells your body uses to repair your organs and tissues as you age. He’s working on ways to deploy stem cells that are more effective for longer periods, and to bank the cells in babies’ placentas, freezing them at deep-space temperatures, to be available 30 and 50 and 100 years later, so that as a person ages, the stem cells making repairs are as fresh as possible. Babies born today will be dipping into their own stem cells to keep them strong and healthy in 2116. And by then, we can only imagine how effective those treatments will have become. Hariri makes the analogy of keeping a backup disk of Microsoft Office in a drawer for when the programs become corrupted on your hard drive. Excel seems balky? Just reinstall the software. Starting to get arthritis? Just hook yourself up with your own proto-self.

The capabilities spiral upward from there. HLI has an expert in the microbiome, the galaxy of bacteria cohabitating in your body that make you as much an ecosystem as you are a single organism. The company has imaging that can find tumors as small as 2 millimeters across—the tip of a sharpened crayon. And once a surgeon removes that cancer, the company will sequence its DNA to get its chemical signature. Before it returns, the plan goes, your blood will show signs that it’s trying to come back, and doctors can treat it.

Look a little further ahead, and we may be coming to an era when we can prevent many of these maladies before they even begin. Synthetic biology—the use of computers and machines to help us optimize our bodies—will let us tinker with the genes that determine so much of how we age and wear out. Once you can edit your genes and replenish your stem cells, many of the greatest threats to our health will carry the same ring as polio or diphtheria.

All of that sounds fantastic, right? But it’s one thing to sketch it out. It’s entirely another to put together the sort of team that can command both $300 million between its A and B rounds of funding and a roster of all-world scientists from an array of disciplines to put in motion. Making those connections, Hariri says, is where Diamandis shines.

“Much to Peter’s success, he brings people together who normally would not interact or exchange ideas,” Hariri says. “Peter becomes the catalyst for that. He amplifies his creativity through connectivity, one of his greatest talents.”

And if we’re going to try to live forever or even stay spry into our triple digits, as Diamandis wants to see happen, then maybe we can finally get some work done around here.

***

This is the trouble when you’re trying to think on a timescale better suited to oak trees or giant tortoises. You’re just not likely to be around to see it all transpire, even if, like Diamandis, you’re optimistic about the curve the species as a whole is traveling. The New York Times review of Diamandis’s most recent book, Bold: How to Go Big, Create Wealth and Impact the World, a treatise on how to imagine and build disruptive business ventures, called it “inspirational, even if it is sometimes comically hyperbolic.” It’s not the timbre of Diamandis’s thinking that freaks people out—nearly anyone can acknowledge a general sense of an advancing good somewhere—it’s the degree to which he takes it.

We’re enjoying an inexorable march toward higher living standards and wider access to technology.

In Diamandis’s long view of history, we’re enjoying an inexorable march toward higher living standards and wider access to technology. His first book, also co-authored with Steven Kotler, put it right there on the cover as Abundance: The Future Is Better Than You Think. A 2012 TED Talk articulated this vision with the same literally starry-eyed optimism that, in Diamandis’s framing, contradicts what he sees as the myopic gloom of most newscasts. “We truly are living in an extraordinary time,” he told the crowd, “and many people forget this. And we keep setting our expectations higher and higher.”

JEFF KATZ

JEFF KATZ

It’s not just the visible stuff—the cars and planes, space travel, refrigerators, medicines, televisions, smartphones, wireless internet, GPS, digital cameras, Skype, robotics, 3-D printing or solar panels. It’s in the widespread abatement of poverty, shrinking child mortality, rising literacy, democratization of the world’s information. When Diamandis gets rolling on this gospel, it’s partly with a fanboy’s enthusiasm for the whole of human achievement, but it’s also a rallying cry to the thinkers and doers of the world to stay committed to making the world a safer, healthier, smarter place. “It is about creating a life of possibility,” he says in that talk, and he has made a career of steering large sums of money toward that thesis.

Related: How to Be a Better Thinker, Innovator and Problem Solver

In keeping with that goal, the XPRIZE model is simple and beautifully empowering. It searches for problems that require a breakthrough solution—something so far off, so daft, that even approaching it requires a wholesale rejection of past thinking—and gets cash bounties from philanthropists and corporations to entice geniuses, often dormant ones, to take a crack. It kicked off the commercial space travel boom by incentivizing the Ansari prize that awarded $10 million to put a ship into orbit in 2004, just eight years after the prize was announced. It spurred huge breakthroughs in oil spill mitigation during the Deepwater Horizon crisis and is now nudging the world to build the first working tricorder, the device that Star Trek doctors used to scan patients for any and all medical information.

The open competitions wind up leveraging huge amounts for payouts: The teams that chased the Ansari XPRIZE, for instance, spent a combined $100 million toward winning $10 million. The competitors are often nimble teams, small groups that come at huge problems in unorthodox ways. Diamandis is such a believer in this kind of open meritocracy that he extols it as one of the overlooked ways to drive world-changing projects. He got the idea for incentive competitions when he learned, in a detail dust-covered by history, that a then-underdog Charles Lindbergh made his pioneering 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic to win a $25,000 prize.

It’s no coincidence that aviation keeps motivating the big leaps in Diamandis’s life. Flight, after all, is foremost about saving time, compressing journeys that once took weeks or months into a matter of hours. Why, you may be in a plane as you read this very story. And think of how much younger you’ll be upon your arrival than if you’d taken the voyage by ship or by wagon or by foot.

If the XPRIZE HQ looks like a museum to space travel, Diamandis’s open office, right among his people, could be the gift shop. His shelves are awash in family photos, books and Space Age kitsch: plastic rockets (including a SpaceX model), wind-up rockets, a lava lamp in the shape of a rocket, Star Trek toys (including a Spock bobblehead), Curious George as an astronaut, G.I. Joe as an astronaut, and a SpaceShipOne toy, still in its package, that’s showing the sun-faded wear of an entire decade on the shelf. That breakthrough by scientists, engineers and dreamers has eased seamlessly into the culture at large, where science fiction and reality so often merge quietly in the very recent past.

JEFF KATZ

JEFF KATZ

As for Diamandis’s workspace, well, far from the slab of burnished redwood and leather you might expect, it’s an ordinary treadmill desk. He says the pedometer on his wrist tallies something like 5,000 steps during any given hour’s worth of conference calls. (He’s into giant leaps, but first a man must take many, many small steps.) “Sitting is the new smoking,” he says. “I take as many meetings as I can as walking meetings. I’ll meet people at a coffee shop and go for an hour walk.” He now reads books almost entirely via headphones, during walks. Lately, for fiction, he’s been listening to Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves, a sci-fi novel in which mankind has to figure out how to survive the moon’s shattering into chunks; naturally he’s latched onto the role of asteroid and comet exploration in this tale. His nonfiction read lately? How Not to Die, a treatise on how food can prevent disease.

Scarcity, Diamandis likes to say, is contextual. In the past 200 years, for instance, technological breakthroughs have turned aluminum from a common but unusable metal to one of the world’s cheapest, most useful materials. The other facet of Diamandis’s approach is the appreciation for exponents. A small number may double each year and remain, for several years, still pretty small. But two doubled 10 times gets you past 2,000. Ten more doublings, you’re above 2 million. Ten more doublings, you’re past 2 billion. If this is the manner in which you see wealth develop, then the only scarcity becomes time itself. You absolutely want to stick around for that 30th year, after all, when it’s worth more than the first 28 combined.

“People just don’t understand the power of exponentials,” he says. “We’re in a period of time where biological sciences and technologies are growing exponentially. Data science is growing exponentially. And our ability to understand our body and then being able to actually engineer it to be healthier and live longer is happening right now. It’s during our lifetimes. The next decade, it’s all happening.”

“I’m 55 years old. I’m shooting for a multihundred-year lifespan. That’s my goal. If you don’t shoot for it, you’re not going to hit it, right?”

This is not to say he’s leaving it up to tomorrow to see the future. Diamandis’s current approach to living to see 700, in fact, probably looks a lot like yours. Daily exercise. Eight hours of sleep a night. Maybe a vegan diet… he’s not sure on that one yet. Meanwhile he’s taking supplements that might stave off cancer and is trying Modafinil, a so-called smart drug, and Metformin, a drug usually given to diabetes patients that might also aid longevity. Diamandis admits these amount to personal experimentation. But he’s keeping one baseline certain: “Attitude is one of the most important things. I fundamentally believe this. I’m 55 years old. I’m shooting for a multihundred-year lifespan. That’s my goal. If you don’t shoot for it, you’re not going to hit it, right?”

Don’t believe it will happen? Well, to find out whether he’s wrong, all you have to do is outlive him. Best of luck on that.

Related: 21 Life-Truths From the Man Behind XPRIZE

This article originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of SUCCESS magazine.