I will never forget the first and only time I ever visited Branson, Missouri.

It was a short trip, and I was looking forward to visiting the “Live Entertainment Capital of The World.” Unfortunately, the entire experience was spoiled by an incident at a popular breakfast restaurant.

Shortly after being seated, I was greeted by my server. “What brings you to town?” he asked. I was traveling on business and planning to open a new franchise in the area, I said. For the next few minutes, he asked me repeatedly for details about my stay—about my hotel and my full trip itinerary. And why would an existing franchise owner want to sell to me, he asked before ever taking my breakfast order.

All I wanted was an omelet. Instead, I felt I was getting an interrogation.

The persistent questions alone were making me uncomfortable. But his shaved head, military-style jackboots and the bullets tattooed on his finger put me on guard—so I finished my meal and exited quickly. Later, I discovered that his tattoos were gang-related and affiliated with local white supremacist groups.

When I returned to my office in Atlanta, I shared the nerve-wracking experience with my manager, one of the few Black directors in the company. “Yeah, these things happen. Bet you’ll never go there for a vacation,” he said sarcastically. As a Black professional, he had been through his own set of uncomfortable interactions traveling on business and was all too familiar with the array of characters you meet and the variety of tactics used to wiggle out of uncomfortable environments. And despite his willingness to let me vent, I couldn’t help but feel like I needed more from him, from my coworkers and from the company I worked for.

The incident wasn’t their fault, but it occurred while I was conducting company business, and it affected my work for weeks. Anytime I thought about the trip or the project came up as a topic of conversation in meetings, I found myself spiraling down a path of worst-case scenarios: What if the server had put something in my food? What if he wrote down my name from my credit card and used it to find out who I was? What if he knew the front desk agent and found out exactly what hotel and room I was staying in? I was bothered by how easily something horrific could have happened—and by how casually my coworkers reacted to the incident.

There seemed to be an expectation that I simply let it go and not allow it to distract me from my work. But it wasn’t that simple. I needed help, and instead was left disappointed at the absence of company support for a work situation like this.

Fast-forward almost six years, and in response to social uproar, words such as diversity, equity and inclusion are often touted by employers as a core value. Yet, despite these efforts, recent polls have shown that 97% of Black workers did not want to return to the office after growing accustomed to working from home. Among the leading causes of this reluctance was their unwillingness to deal with racism in the workplace.

Turns out, whether I was traveling on business or not, the likelihood of me being impacted by racism was still present. And as someone who has dedicated his life to exploring the intersection of work, culture and money, I couldn’t help but think about the financial implications.

The importance of being an ally

Besides my Branson business trip, I’ve unfortunately had numerous and varying degrees of racist interactions at work. From offensive remarks about my culture to me being used as a symbol of progress, I’ve witnessed a wide spectrum of macro- and microaggressions. Looking back, having an ally would have certainly helped alleviate the pain.

Quite naturally, while these events were unfolding, I’d find myself leaning on the shoulders of the handful of Black leaders in positions of power for guidance. Looking back, I regret putting that pressure on them; I know now that I was hardly the only one looking for help or protection. It would’ve been far more helpful to me if a white colleague—preferably a leader—had offered support or helped to escalate an issue. By using the influence and privilege that comes with being part of a majority group, someone in that position might have helped reduce my sense of vulnerability or feelings of isolation. Conversely, asking a Black leader to raise an issue on my behalf would also mean asking them to accept the risk of any backlash that may come my way.

This is difficult to accomplish for new or younger employees who don’t have extensive or influential professional networks. Instead, in an effort to avoid conflict altogether, they are far more likely to quit, which could have a negative impact on their earning potential, retirement account contributions, health care coverage and other financial employee benefits.

Furthermore, they run the risk of having to explain to future hiring managers why they may have left a job suddenly or spent such short stints of time at a previous employer. Having allies at work isn’t just about having a confidant or an enforcer of policies. Allies are critical to helping minimize turnover and drive performance.

The impact of toxic work environments

Early in my career, while working multiple jobs to pay my way through grad school, I hit a breaking point. While sitting at my desk one day, I suddenly felt a cramp in my neck that just wouldn’t go away. After visiting a specialist, taking medication and undergoing hours of electrostimulation, I learned it was all stress-related. From that point on, I’ve been mindful of how hard I push myself so I don’t end up in that predicament again. But unfortunately, even after this experience, I failed to realize the full range of ailments a poor work environment could have on my overall health.

Years later, at the peak of my corporate career, I developed a slight eye twitch. Shortly after, I noticed the gradual weight gain. As my company went through several organizational changes that would ultimately lead to repeated layoffs, my heart rate elevated and I was constantly fatigued. And whenever there was a hot-button racial issue making waves in the mainstream media, I’d find myself struggling at work knowing my community was under fire.

In an effort to soothe these discomforts at the office, I would decompress at happy hours, hire personal trainers and purchase loose-fitting clothes—all of which impacted my ability to save and invest. Once again, I found myself stuck in a cycle of working for money to pay for the ailments brought on by work. Only in my mid-30s, I was beginning to feel the effects on my mind and body.

According to the American Psychological Association, some of the leading causes of stress in the U.S. are money and work. Factor in the threat of an economic downturn, which often leads to job loss, and it’s safe to assume that more stress and the ailments it causes will all be on the rise in the near future. Considering the economic fragility of Black households, this also foreshadows difficult times ahead.

Recent surveys by the Pew Research Center have revealed that despite Black Americans being just as likely as Americans overall to work more than one job at the same time, just 36% of Black households have a three-month emergency fund. So today, though I can proudly afford specialized medical or wellness services, therapy or to take an unpaid leave of absence, the majority of people in my community can’t.

How reevaluating your career length can alleviate these challenges

Despite the progress our country has made and decade-long commitments by corporations, there are still sizable wage gaps by race and gender. White men are still far more likely to be promoted to leadership positions than any other group. And the racial wealth gap has stubbornly persisted and is slated to widen in the coming years. Through it all, I remain optimistic that better days are ahead, but I manage my finances and career more pragmatically.

It’s convenient—and perhaps, natural—to allow negative data and news cycles to shape your beliefs and approach to work. But I’d challenge you to take a simpler, albeit counterculture approach to thinking about your career. And there’s no better question to ask yourself than, “How long should it be?”

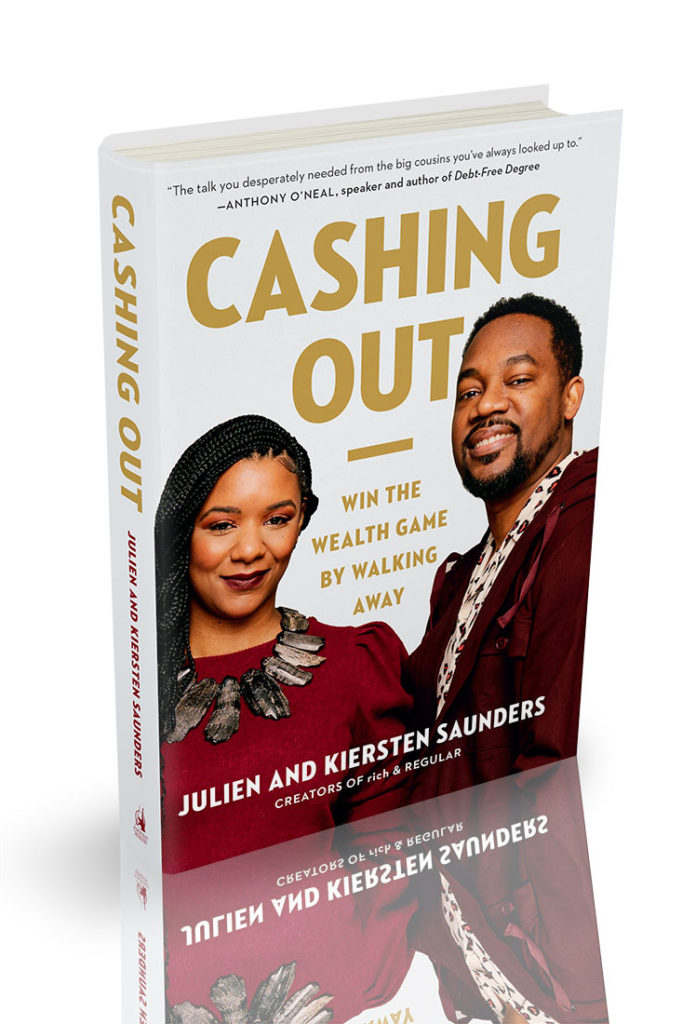

In our book, Cashing Out: Win The Wealth Game By Walking Away, my wife, Kiersten, and I propose that you completely reevaluate the typical approach of working for 40 to 50 years and plan to exit the workforce after only 15. You can do this by thinking about your 15-year career in three five-year sprints to include aggressive debt elimination, investing above and beyond standard rules of thumb and developing skills that allow you to maximize income both inside and outside of work. If you’ve followed this framework well, you’ll end your 15-year career completely debt-free, having invested consistently for over a decade and with a wide range of income sources you can tap into as needed. Most importantly, you’ll eventually insulate yourself from many of the ills and frustrations that plague most working families.

Today, in my early 40s, I’m old enough to remember when women didn’t have professional sports leagues, when smoking on airplanes was allowed and when vegan cuisine was jokingly referred to as bird feed. These memories have taught me that, despite mounds of data and political pressure, we are perpetually slow to change until we’re forced to do so. So although I’m hopeful of change at work and wish to live in a world where everyone feels safe and valued, the unfortunate reality is, change may not happen anytime soon. And rather than wait, employing an individual solution to find your own financial freedom is the best course of action.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2022 issue of SUCCESS magazine. Photos by ©Phyllis Iller Photography