As I open the door of the beat-up burgundy sedan, I’m apprehensive. Ulysses “US” Floyd tells me the seatbelt for the passenger side of his car is broken. “It shouldn’t be a problem though,” he says. The seatbelt, I will soon learn, should be the least of my concerns. Before this trip, I’d never witnessed a drive-by shooting.

Floyd is showing me around the South Shore and Woodlawn neighborhoods of Chicago, two communities that have some of the highest homicide rates in the city. He’s an outreach worker and supervisor for CeaseFire Chicago, an organization that hires people—most of whom are ex-gang members who have served time in prison—to go back into their communities to prevent shootings and violent crimes.

Floyd stands 5-foot-6 and has graying cornrows pulled back into a ponytail. He’s wearing gray pants and a zip-up hoodie. He introduces himself, somehow ignoring the persistent beep, beep, beep of the seatbelt alert: “I’m an ex-dope dealer and ex-gang leader.”

STEPHANIE STONE

Floyd says he joined CeaseFire Chicago in the mid-2000s after serving time for drug-related charges in the 1990s. He wanted to help fix some of the problems he was a part of creating during his days in a gang. Working with CeaseFire, he says, is his life’s greatest accomplishment. He prides himself on his ability to mentor and rehabilitate young men in the community who are struggling.

Related: John Wooden’s 7-Point Creed: ‘Help Others’

“I helped start this,” he tells me. “I used to be a part of the problem. I saw these guys get shot and killed and I said, ‘I want to be a part of the solution.’ ”

It’s 3:30 p.m. on an uncharacteristically warm Tuesday in November. High school students have just been released from school. The businesses in this neighborhood have faded, and the homes have peeling paint and shabby front lawns. Floyd spends the next hour and a half telling me jaw-dropping stories as he drives me through South Shore and Woodlawn, taking me to where the most violent crimes occur, the places he calls “hot spots.”

The crime rate in Chicago is well established. In 2016, the city saw 762 murders, the highest number in two decades. And Chicago alone contributed to about half of the entire nation’s homicide rate increase in 2016.

It’s not long before we hear the gunfire. As we drive through Beat 414 just south of the South Shore neighborhood—where Michelle Obama grew up—we hear a loud pop, pop, pop, pop, pop. Floyd checks his rearview mirror as I reflexively duck my head and slide down on my seat. The gunshots are loud and quick, and the sound pierces the calm of our friendly conversation.

When I first heard the gunshots near our car, it felt like my heart might stop on the spot. I had never heard gunshots before. I felt frightened and anxious, adrenaline pumping through me. I assumed Floyd was equally scared and would speed away at 60 mph, but he didn’t. His demeanor was calm and serious. He peered back into his rearview mirror to see if anyone had been shot before speeding away.

The shots came from a black SUV two cars behind us. Someone was shooting at a group of young men standing on the corner. As the bullets flew, the men on the street sprinted away. Floyd looks in his rearview mirror and tells me it doesn’t look like anyone was hit. I notice that no one outside seems particularly fazed by the piercing gunshots.

About 20 minutes later, we drive back to where the shooting occurred and life seems wholly uninterrupted. Children have gathered again on the street. The crossing guards are still outside, smiling.

There are no police officers in sight.

It’s as if nothing happened.

***

CeaseFire Chicago was founded in 2000 by Gary Slutkin, M.D., a professor of epidemiology and international health at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health. Slutkin had spent years abroad working with infectious diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis and AIDS. When he moved back to Chicago, he couldn’t help but notice the news stories, day after day, about young black men in Chicago being shot. He studied the data and was surprised by what he noticed: Violence looked a lot like an infectious disease.

STEPHANIE STONE

“I saw that I was looking at the same types of maps, graphs and charts of every single other infectious disease I ever worked out,” he says. “It seemed to me like a giant thing was missing in terms of the contagious nature of this.”

Slutkin investigated what the city was doing about this problem, and none of the solutions made sense to him. Increasing prison sentences didn’t stop the violence. Neither did attempting to fix all societal standards, because problems such as poverty, education and hunger cannot be fixed overnight. The way people were treating the ravaged neighborhoods of Chicago reminded Slutkin of the early days of AIDS, when society thought of those affected as bad people and not merely a product of their unfortunate circumstances.

Related: 6 Success Lessons I Learned From the Streets

“It came to me that we should try something new, try something that operates in the way that we fight every epidemic, not just this one,” he says. Slutkin set up a model that mirrored public health models for fighting infectious diseases: 1) Hire new workers; 2) find the people who are most credible and trusted and train them so they can spot early events (in this case shootings) to stop the spread; 3) help cool people down and change their behaviors; and 4) use outreach and public education.

“It’s really that simple,” he tells me. “It’s the same thing as Ebola, cholera or tuberculosis.”

Members of the organization use data to target the most dangerous neighborhoods in the city, and then from there, they identify the specific areas within the neighborhoods that have the most crime. “It’s almost insane to say, ‘Let me work right where they have the most shootings and killings,’ but that’s how we’re data-driven,” says LeVon Stone Sr., CeaseFire Chicago’s program director. “We want to go where the most problems are at.”

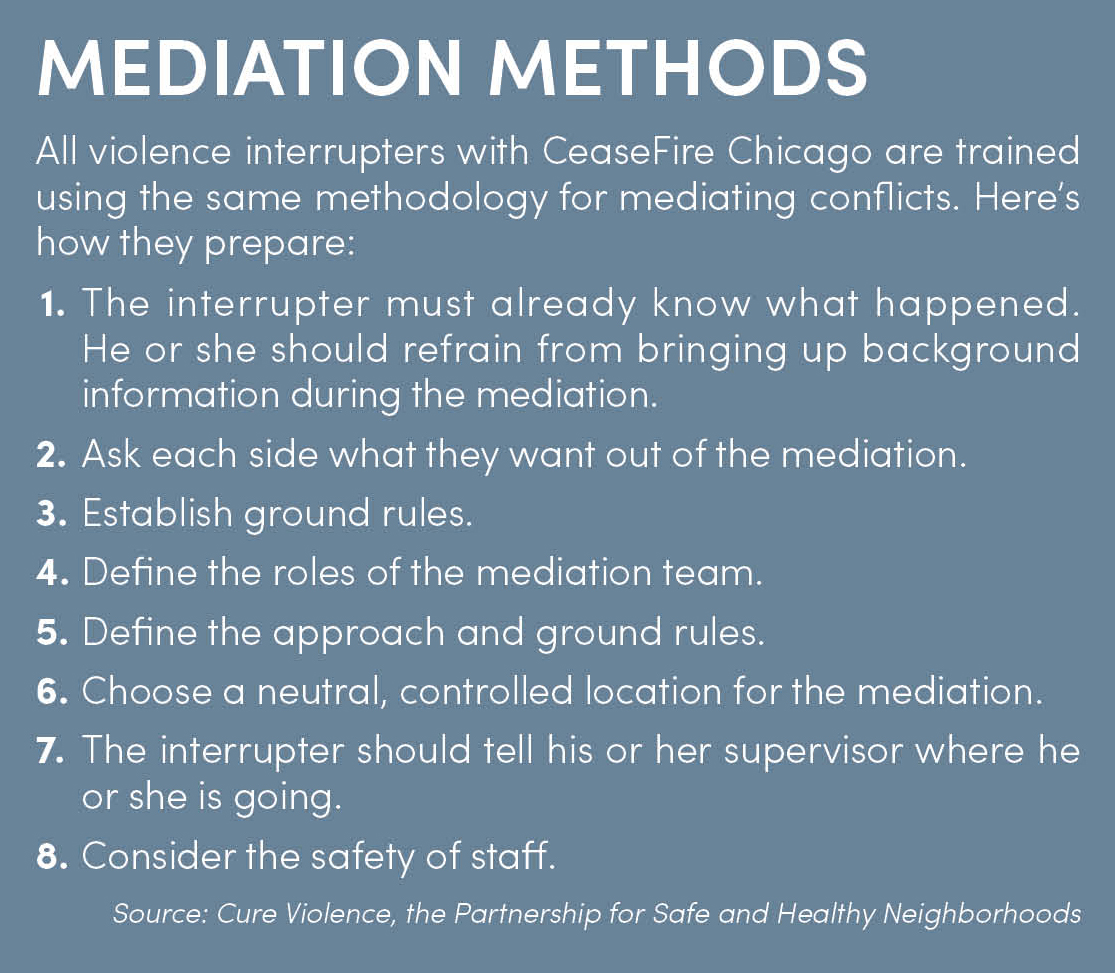

CeaseFire has four types of employees. There are violence interrupters, who are boots-on-the-ground preventers trying to stop conflicts as they happen. They step in during an escalating argument or bring people together to resolve disagreements. There are outreach workers, who identify high-risk individuals in the community and work with them to improve their lives. For example, a high-risk individual is typically someone between the ages of 16 and 25, recently released from prison or recently shot, active in a violent street organization, or a known weapons carrier. An outreach worker would then help the high-risk individual land a full-time job or earn his or her GED certificate.

ED KASHI/VII/REDUX

There are also hospital responders, who arrive at one of the Level I trauma centers in Chicago after a stabbing or shooting occurs to work with victims to prevent retaliations by calling the violence interrupters to help defuse anything that might be happening in the community. And there are case managers, who work with trauma patients from the hospitals on an ongoing basis—sometimes for years at a time—by helping them reintegrate into the community in a healthy, productive way.

Slutkin’s model proved highly effective. In the first year of implementation, one community in Chicago had a 67 percent reduction in shootings. Later evaluations have shown violence reductions ranging from 40 to 70 percent when the program was in place across seven communities. The number of active CeaseFire employees varies at any given time due to fluctuating funding from the state, but data shows that when CeaseFire is at its peak—meaning it has the most workers in the most communities—shootings and retaliations diminish significantly. Of course, it’s hard to quantify murders that don’t take place: the number of lives saved, of families undisrupted by violence or incarceration.

ED KASHI/VII/REDUX

“Our job is to stop shootings and killings on the front end, and we’re successful at that,” says Andre Thomas, a CeaseFire hospital responder. “But how are you gonna get credit for something that never happened? How are you going to document that? It didn’t make the paper.”

***

Since proving its value in the mid-2000s, CeaseFire expanded nationwide, changing its name to Cure Violence in 2012, which operates in more than 20 cities in the U.S. and eight other countries. The program has also received notable publicity, including a New York Times Magazine cover story in 2008 and a documentary film, The Interrupters, in 2011.

The U.S. Department of Justice released a report in 2007 titled “Evaluation of CeaseFire-Chicago” that documented the effectiveness of the organization’s initiatives. Slutkin says soon after, Baltimore and Los Angeles contacted him looking for guidance in implementing similar programs.

Violence interrupters, hospital responders, outreach workers and case managers at CeaseFire’s headquarters at the University of Illinois at Chicago all say the same thing: What makes them successful is their strong bond with the people in their respective communities.

“We’ve got relationships. We’ve built trust in the community.”

“We’ve got relationships. We’ve built trust in the community,” says Stone, the program director. “The only reason CeaseFire is effective is because it’s a grassroots organization that’s employing and working with the community. You can’t do this without the community. Period.”

The organization also keeps its interactions with community members confidential, which causes some tension with the Chicago Police Department.

“The confidentiality is what allows us to do what we do. It strengthens us,” says Chico Tillmon, a CeaseFire program manager in the North Lawndale neighborhood. “We have individuals who tell us what actually happened. The thing that makes us powerful and what becomes problematic between us and the police is we have the relationships they don’t, where a person is comfortable enough to say, ‘Hey, I’ve got a gun. This is what’s going on. This is what’s gonna happen.’ ”

Donya Smith, 26, is the youngest violence interrupter in the program. He works in Englewood, one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Chicago. Smith, who wears a letter jacket with the word geek on it and a flat-brimmed Chicago Cubs hat, says he had an incident in his neighborhood that perfectly illustrates how important CeaseFire’s trust with the community is. At 3:30 a.m. a man he knew called him and asked him to come over because he was scared for his life. When Smith arrived at the man’s house, a group of men were lined up on the front lawn ready to shoot the minute the caller stepped outside. Smith knew the men outside, too, and was able to defuse the conflict using the methods he learned at CeaseFire.

“I ended up bringing the guys together,” he says. “We resolved the issue. Now I see the guy’s mother, and she’s always hugging me. Like I saved her son’s life.”

Smith was skeptical of CeaseFire as a teenager. That is until he was shot at 21. “It’s crazy, but getting shot was the best thing that happened to me in my life. It just showed me how to appreciate life. In the blink of an eye, it can be gone.”

Related: 5 Ways to Be More Grateful on the Daily

After being released from the hospital, Smith started spending time with CeaseFire workers as a volunteer. He figured the positive influences would keep him away from the violence on the streets. As he spent time with the interrupters, he decided he wanted to help improve the situation in Englewood himself and was eventually hired. He has been with the organization officially for three years.

COURTESY OF DONYA SMITH

“Day to day, I do this ’cause they’re my people,” he says.

Stone says many men in CeaseFire, including himself, have taken similar paths. Stone, who is in a wheelchair, was shot and paralyzed from the waist down while attempting to intervene during a conflict. Despite that, he still went on to mediate conflicts because they involve people he cares deeply for. “Some of us took the scenic route, and some of us took the expressway,” he says. “To me, it’s not how you start, it’s how you finish. I’ve had the privilege to do it all. Unfortunately, I was shot and paralyzed at 18. But I made the best of it. Some of those things I’d do again if I had to.”

The biggest ongoing challenge CeaseFire Chicago faces is funding. Between salaries and administrative costs, the program had an overall budget of approximately $5 million in 2016. In the 2015 fiscal year, the program was initially budgeted to receive $4.5 million from the state of Illinois. That budgeted amount was then lowered to $1.9 million, and subsequently suspended completely in March 2015 due to a state budget shortfall. (The state of Illinois has not passed a budget in over 18 months.) The program had received no state funding between March 2015 and late November 2016 until stopgap funding provided them with $1.3 million, which had to be used by the last day of the year, allowing them to temporarily resume work in 19 communities.

COURTESY OF CEASEFIRE

The vast majority of the program’s funding comes from the state, but there are some other funders, such as Advocate Christ Medical Center, Chicago White Sox Charities, Northwestern Memorial Hospital and the McCormick Foundation. In March 2015, when the state of Illinois stopped funding CeaseFire, it pulled funding for various other state initiatives, too. The state of Illinois has been in a financial crisis for years, with debt that exceeds $187 billion.

Once funding for CeaseFire Chicago was pulled, the city saw a surge in shootings. Thirteen of 14 CeaseFire sites had to shut down or considerably cut back, leaving only one location, which was funded from a different source. Slutkin says shootings went up in all 13 districts where funding was pulled and down in the one that remained active.

Funding has been unstable in the past, and Slutkin says there is always an increase in shootings when CeaseFire doesn’t have a neighborhood presence. The program doesn’t know when its next round of funding will come.

***

Toward the end of my ride-along with Floyd, I hear a semitruck hit a bump on a bridge. The noise startles me. It sounds eerily similar to the gunshots I heard earlier. We pass 79th and Halsted Streets, and I see a CeaseFire bumper sticker on a stop sign with a picture of a young boy and the words, “Don’t shoot. I want to grow up.”

Floyd then takes me to 75th Street and Exchange Avenue, where he said two retaliatory shootings occurred just a few days earlier. One victim was an 18-year-old girl; the other a 58-year-old woman. Both were caught in crossfire, innocent people going about their day. (These two deaths are not verified, as 17 people were murdered that one weekend in Chicago. Because so many people are killed, not all of the shootings make the news.)

The violence here is pervasive and persistent—a lurking, uneasy feeling that never lifts from the residents in these communities. But they push it aside to be there for those they love. Many of the CeaseFire workers said they do this work simply because it feels natural—they would still be doing it without getting paid. Members of these communities, including CeaseFire employees, are willing to put their lives on the line. I’d like to think that I would put my life on the line for my family and friends. But I’ve never had to. These people have to, and they’ve done it.

After my nerves calm down a bit, Floyd tells me story upon story about his time working as a violence interrupter. He once brought several hundred members of rival gangs together in a church in Woodlawn for a peace treaty. He also tells me that if I weren’t in the car with him after the shooting we witnessed in Beat 414, he probably would have driven back to the scene to make sure everyone was OK. This boldness and bravery is apparent in everyone at CeaseFire. Stone and Smith were both shot but still went on to insert themselves into potentially dangerous conflicts in their neighborhoods.

Because CeaseFire is part of the University of Illinois at Chicago, all full-time employees are eligible for tuition waivers, which cover education at the university. Although CeaseFire is managed through the university, not every member is employed by the university; some work for local community organizations. However, most of the people I spoke with at CeaseFire had either already completed or were pursuing a doctoral, master’s or bachelor’s degree. Tillmon was in the second year of his Ph.D. in criminology, law and justice studies, while Smith was about to begin his bachelor’s in psychology in 2017.

“We know there’s a possibility for change, and we’re an example of change.”

While I’m chatting with Stone at CeaseFire’s headquarters before my ride-along, he gathers his thoughts and looks at me contemplatively. “We’re a total example of change. If you were once shot, that didn’t stop you. If you were once incarcerated, you didn’t let that stop you. We know there’s a possibility for change, and we’re an example of change.”

Related: If You Change Yourself, You Can Change Your Life

This article originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of SUCCESS magazine.