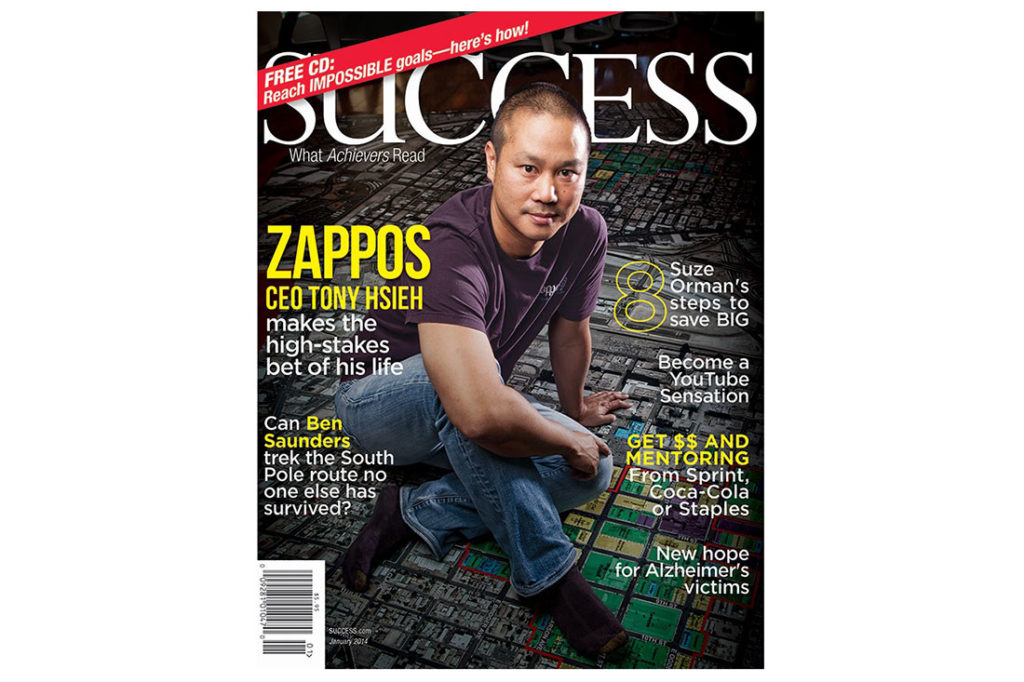

Tony Hsieh, a true visionary and inspiring leader, died on Friday, Nov. 27, 2020. For him, culture was Job No. 1—his philosophy about delivering happiness, to customers and employees—because by getting that right, everything else just worked. In this 2014 cover story for SUCCESS magazine, you can learn more about the former Zappos CEO and his innovative leadership. Rest in peace.

Tony Hsieh is pounding on an overturned garbage can in a performance hall full of people. Dust flies. People are laughing.

What’s funny isn’t that the CEO is banging on a garbage can as if it’s an oversized bongo, but that he doesn’t seem to have rhythm. He can’t find the beat.

His performance at this quarterly Zappos All Hands Meeting follows that of an employee who delivers a soulful rendition of “Cups” (“When I’m Gone”). She’s accompanied by other Zapponians using plastic cups to tap out the rhythm. Everyone’s in sync. And then there’s Tony with his garbage can.

Tony (everyone goes by first names here) is not a center-stage kind of guy. He’s certainly at the center of activity; his no-holds-barred thinking fosters tsunamis of innovative ideas. But he’s soft-spoken, introspective, maybe even a little shy.

He’s also a nonconformist. He’s hosted pajama parties for employees and participated in shave-your-head day at work. He’s got a human-sized blow-up monkey that’s often in his chair if he’s not at his desk. At the recent ribbon cutting for Zappos’ new headquarters, amid the city dignitaries in their shiny suits and Zappos folks in jeans, there was Tony standing next to a llama. And not the blow-up kind. Creating fun and a little weirdness is one of Zappos’ 10 core values.

This All Hands meeting in late September caps a busy week for Zappos, with most of the 1,400-plus employees having moved from their Henderson, Nev., headquarters into their new home in the former Las Vegas city government complex. As big as the move is for Zappos, it’s monumental for Las Vegas. City council members characterized it best when they authorized the deal in December 2010.

“In just a conversation, today, at this meeting, the values of downtown properties have changed,” Councilman Steven D. Ross said.

“This transaction is going to forever affect the social fabric of our community,” Mayor Oscar B. Goodman said. “The way we think about ourselves and our inner core will be different from this moment forward.”

The effusive comments continued. Seated in the audience, listening, Tony wiped an eye.

It’s been an emotional ride and it’s far from over.

Tony Hsieh (pronounced Shay) was an accidental corporate CEO. Right out of Harvard and bored with his day job at Oracle, he and a college buddy built a tech company, LinkExchange, sold it in 1998 to Microsoft for $265 million, then founded a venture capital firm called Venture Frogs. They were happily funding other startups when the dot-com boom waned. One company in their portfolio was online retailer Zappos.com. As other potential funding sources dried up, they had to decide which companies they’d fund for another round. They liked the scrappy Zappos guys who wanted to turn retail upside down by selling shoes, of all things, over the Internet.

Fred Mossler, who had worked in shoes for Nordstrom, joined Zappos in 1999. “We worked feverishly to build the business, and it turns out that the funding [from Venture Frogs] only gave us about four to five months’ worth of runway. We tried to find other sources and we couldn’t. It came down to the eleventh hour, and we were closing up shop. Then we all went out to lunch and Tony called and said that if we met certain requirements, they would fund us another three months. One of the requirements, was that we move out of our office and into his loft in [San Francisco], and he would join us as co-CEO.”

Tony would dole out money in increments, telling the Zappos guys that if they made enough progress, he would fund another round. Behind the scenes, to keep Zappos afloat, Tony was selling his personal real estate, sometimes at fire-sale prices.

Money was just one worry. They also had to figure out how to attract top brands, how to ship as efficiently as possible, how to get customers to buy shoes they’d never tried on. “It was exhilarating,” Fred says.

In 2004, like a pied piper, Tony led Zapponians in a move from San Francisco to the Vegas suburb of Henderson. In the the roller-coaster ride of 2008–2009, Zappos laid off 8 percent of its employees, hit $1 billion in sales and debuted on Fortune magazine’s “100 Best Companies to Work For” list. Later that year, Amazon bought Zappos in a deal valued at $1.2 billion that allowed Zappos to continue operating as an independent entity.

Meantime, Tony, Fred and team distinguished the brand by focusing on exemplary customer service, which they achieved by creating a culture that empowered employees to do whatever they thought best to satisfy customers. Zappos’ product lines expanded to include other apparel as well as luxury brands, and the company grew.

“Starting out in that two-bedroom apartment, never in my wildest dreams did I think that we would end up where we are today,” Fred tells me in a conference room in the new headquarters. As he finishes his sentence, the door flies open and a startled woman bursts in. “I thought this was a stairwell!” she says. Everybody erupts in laughter.

What began as a search for more office space ultimately morphed into the transformation of a city. Tony has dedicated $350 million to the Downtown Project, a separate entity from Zappos launched in 2012. The objective is to revitalize downtown Las Vegas by acquiring and developing real estate, and attracting and funding early-stage tech companies, other small businesses, educational opportunities and entertainment. The aim isn’t solely economic, although this hard-hit city could use all the help it can get.

“The long-term goal is to help make downtown Vegas a place of inspiration, entrepreneurial energy, creativity, innovation, upward mobility, discovery and all that good stuff,” Tony tells me as we talk in the living room of one of three connected apartments where he lives, works, parties and collaborates some 20 stories above downtown. “That’s good for Zappos. It’s good for the community and city. And that’s the type of place I want to live in.”

Already, there’s a vibrancy here that’s infectious. Jen McCabe came for a visit and essentially stayed, first with robotics company Romotive and now as “hardware sorceress,” recruiting and funding companies through the Downtown Project’s Vegas Tech Fund. “I think for people who are passionate about what they do, downtown provides this strange kind of incubator where you immediately feel the energy and you know that it’s kind of conductive. And you can build whatever you envision,” she says.

Beyond the wide-open opportunities here, the Downtown Project represents something else, says Andy White, head of the $50 million Vegas Tech Fund. “It’s one of the few times in life [when] you have a chance to make a conscious decision whether you want to be a part of this much bigger thing than yourself.”

Tony quotes an interesting statistic: Historically when a city doubles in size, innovation and productivity increase 15 percent per resident. But when companies get bigger, productivity generally goes down.

“Most innovation actually comes from something outside your industry being applied to your own, so it’s really dependent on serendipitous interactions or seemingly random encounters,” he says. “If you get enough people close enough together, they’re going to collide more often, and just statistically those collisions will result in more collaboration, more creativity, more ideas.”

Serendipity is a common theme in Tony’s life and work. It played a role in his joining Zappos and it has led to the move downtown and to the Downtown Project.

Initially, as Zappos outgrew its offices in Henderson, the thinking was to buy land and build a self-contained Silicon Valley-style campus. Tony and Fred were talking about these ideas while having a drink at Downtown Cocktail Room when bar owner Michael Cornthwaite suggested moving Zappos downtown. “Michael is super-passionate about the potential for the downtown, and the idea sank in,” Tony says.

To be clear, downtown Vegas is on the other side of town from the glitzy Las Vegas Strip. In some ways, it’s a world away. If you think of Elvis Presley’s Vegas or the Rat Pack’s, you’re visualizing downtown with its landmark casinos like El Cortez, which is still in operation, and its “Glitter Gulch” of iconic neon.

There have been efforts in recent years to capitalize on this cool retro vibe. One example is the Fremont Street Experience pedestrian mall.

But in the bright morning light, downtown can still feel a little down on its luck. I pass a darkened doorway and a woman peers out with bright blue eyes and a tanned face etched with wrinkles. She’s hunkered down on shopping bags and newspapers. “I’m just trying to stay out of the wind,” she says. “Do you have a cigarette?”

Although the homeless presence is obvious, it’s not what it used to be in the early 2000s. “The area was totally dead, yet full of check-cashing businesses, souvenir shops, lots of homeless and a Payless Shoes,” Michael says. To open his bar, he had to wait through two years of renovations to bring the entire building up to code. He subsequently developed The Beat coffee house inside a medical complex-turned art gallery called Emergency Arts.

Michael remembers his early conversations with Tony. “It was amazing to talk to someone who really understood where I was coming from and the potential that lay ahead,” he says. “It wasn’t me preaching—it was more like a real exchange of ideas and thoughts. Tony understands passion and its value in a happy life, as well as in business and community. I was going home every night and getting so excited about the involvement of Tony that I would have to stop myself and think, This is too good to be true.”

Other magical moments followed—like the time Natalie Young stopped by The Beat and mentioned how tired she was of working in restaurants on The Strip. She said she planned to leave Vegas to open her own place. Michael introduced her to Tony, who persuaded her to stay. Natalie’s Eat became one of the first businesses funded and mentored through the Downtown Project. Nowadays, Eat does a booming breakfast and lunch business, and she has another restaurant in the works.

But, to back up a minute, I ask Tony how he went from moving Zappos downtown to transforming a city. “I guess, to me, it seemed like the next logical evolution,” he says. “If we were going to move here anyway, and I had moved here a little over two years ago, we might as well.”

The ideas started small but grew, Michael says, along with the number of people Tony brought into the discussions. “I just kept stressing the fact that this was the center of a city, not only geographically, but also historically, culturally, economically,” Michael recalls. “We talked about living here, making friends, connecting, working, playing. We talked about each and every property, who owned it and what their specific situation was. I’ve said many times that it was so much fun partially because Tony didn’t think within the same limits and constraints that most of us do.”

Tony asked the head of product management, Zach Ware—who was new to Zappos—for his thoughts about the company’s new campus. “After we spent a few months jamming back and forth on ideas for what downtown could be, Tony asked me to leave my tech position at Zappos and head up the campus project.” Zach refused a few times before jumping in with both feet.

Zach says other things influenced the project’s evolution—reading Edward Glaeser’s 2011 best-seller, Triumph of the City, and meetings at the furniture-design headquarters of Herman Miller Inc. to learn more about how offices are organized. “Ed’s book focuses on this mathematical calculation of 100 people per acre plus ground-level activity equals magic and innovation, [which] drastically changed how we think about how a city operates,” Zach says. At Herman Miller, “we started to think about how offices can be organized to inspire collisions between people from different departments and create activity centers. Their R&D group thinks about how people natively move, how they perceive a space, and we took a lot from that.”

Living downtown at The Ogden, a modern high-rise apartment building, also provided a different perspective, he says.

“Our hunch coming out of all those experiences was that the magic of city development wasn’t in one big idea; it’s in a thousand small ideas,” Zach says. “And in order to make those 1,000 ideas work, there is some infrastructure that we needed to lay.”

With all the talk of collisions and serendipity, I wonder whether goals and plans are four-letter words around here. Tony and his team abhor anything that resembles a constraint to innovation—that’s for sure.

They’ve raised some urban-planning experts’ eyebrows by rejecting the notion of a master plan for downtown. To do so might place too much emphasis on buildings and structures, Zach explains, when the focus really should be on people and experiences. Also, a master plan might foster rigidity, whereas much of the work so far has been done so buildings and their uses can evolve as needed over time, he says.

I ask Tony how he’ll know the Downtown Project has been successful. “I guess one metric will be when people are moving here on their own versus us hosting and recruiting them, and when people just know about it,” he says.

What’s in store for him when that happens? “There are always opportunities for something to unfold into something else,” he says.

But does he try to look into the future to plan for those opportunities? “No, it’s more about what are the different pieces or possibilities now and the different creative ways to piece them together [and] build into something else.”

Tony explains that when he was a kid, his favorite TV show was MacGyver, the action-adventure series about a guy whose resourcefulness could get him out of any fix. “So entrepreneurship is constantly like playing MacGyver with whatever parts you have.”

Another way to describe the entrepreneurial mindset, he says, is like this: “When they want to cook something, entrepreneurs see what’s in the kitchen and make something out of that, whereas people with MBAs go find a recipe and go shopping for each of the elements.”

Tony, the eldest of three sons born to a chemical engineer father and social worker mother, grew up like other first-generation Asian-American kids he knew, he writes in his 2010 best-seller, Delivering Happiness. He was expected to learn two musical instruments; make good grades; get into a good school, preferably Harvard; and end up with M.D., J.D. or Ph.D after his name.

He thinks his entrepreneurial spirit “was just my way of rebelling against having my whole life prescribed for me.”

Tony’s parents abided his childhood entrepreneurship—an ill-fated earthworm farm, a short-lived student newsletter called The Gobbler, and a button-making business that actually was so profitable that Tony passed it on to his younger brothers.

But the path his parents charted for Tony left little room for detours—which he managed to find anyway. Instead of practicing music the required number of hours, he recorded himself practicing and then played the tape in the early morning before his parents would bother to check in on him. He did get the grades and acceptance to Harvard, but he found it hard to wake up early some days. So he skipped a lot of school that first year, but caught up on Days of Our Lives.

He also made lasting friendships, worked odd jobs—wedding caterer, computer programmer, bartender—and honed his entrepreneurial skills. In a particularly innovative endeavor, he invited classmates to divide up study questions and write essays on them to prepare for an exam in a class he’d mostly skipped. He sold the crowd-sourced study guide for extra cash.

Despite the shenanigans, which he disclosed in Delivering Happiness, Tony remains close to his parents. I comment that they must be very proud. “Uhhh, my mom says there’s still time to become a doctor.”

In some ways, college life didn’t end with graduation. As LinkExchange grew, Tony and his partners hired other friends from college, until they ran out of friends. Then they had to hire strangers, and that’s when the fun ended.

Tony stood to make close to $40 million in the sale to Microsoft if he stayed on for another year and would lose about 20 percent of that if he didn’t. But the work wasn’t enjoyable, so he bailed.

That lesson stayed with him and was key in his decisions about the importance of Zappos’ culture.

Zappos is different in a lot of ways. For example, the company has a life coach for employees and library with free books; all new hires train in the call center, no matter their positions; and after training they’re offered about $4,000 to quit—just to make sure they’re committed.

During our visit in late September, we stop on the patio outside the café, where most food is free. An employee is in a recliner with his laptop. “Who needs health benefits when we’ve got a patio!?” he proclaims. “Oh, wait, we have health benefits, too!”

As we stop in the call center, a customer loyalty team member cues “Eye of the Tiger,” and everyone starts pumping dumbbells in the air. Other teams have their own antics for welcoming tours.

Since they’re still unpacking, we don’t get the full effect on this day—as in workspaces chock-full of photos, Christmas lights, stuffed animals and whatnot.

Jamie Naughton, Zappos’ “speaker of the house,” says llamas have been a favorite since Zapponians came to work to find a surprise petting zoo—chickens at one desk, goats at another, the llama over there. They loved the llama so much that they hire him on their own for co-workers’ birthdays or just for laughs.

The quarterly All Hands Meeting is another example of Zappos’ culture. The meeting is a combination of announcements, question-and-answer session, and laughs—with mock Family Feud game show, Zapponians in costumes, door prizes and videos.

With all the hijinks and hilarity, you have to wonder how anyone knows when a line’s been crossed. The answer lies primarily in Zappos’ core values (see below). Developing the list of values took more than a year getting input from everyone. Today the core values provide a compass, a tool that empowers everyone, a set of guidelines used to hire and fire. So when someone crosses the line, it’s usually a co-worker who lets that person know, Jamie says. Even people Tony has hired have failed the core values test, as determined by their co-workers, and subsequently had to leave.

Something else that seems to engender respect and trust is Tony’s manner. People tell me that when they’ve asked for his authorization on something, he assures them that he trusts their expertise and judgment. So they make darn sure their suggestion is sound and then do everything possible to make it work. Once entrusted with that authority, they don’t want to let Tony or anyone else down.

Another thing about Tony is that if you have a problem, employees say he’ll start asking questions, as if peeling back the layers of an onion. When the two of you finally get to the heart of it, he’ll say, “so fix that.” It’s a process that simplifies the problem and empowers the individual, because he or she helped come up with the solution.

Tony Hsieh is 40, unmarried, living in a maze of apartments that also serves as his Downtown Project war room. Renderings, oversized maps, motivational mantras and Post-its with random ideas are everywhere. The kitchens include well-stocked bars and coffee and espresso makers. One room has walls completely covered in live plants. Tony’s home is a stop for all the tour groups. When he’s not working, he’s playing, but usually with people he works with. There’s no “balance”—work-life integration is how he terms it.

Tony has written about getting bored with other projects once the challenges are solved. I can’t picture him moving away from this experience.

“I’m sure there will be other opportunities in the future,” he says. “We’re just focusing on a city. There are people thinking about how to colonize Mars, so that seems like an interesting project.”

Zappos Core Values

• Deliver WOW Through Service

• Embrace and Drive Change

• Create Fun and a Little Weirdness

• Be Adventurous, Creative and Open-Minded

• Pursue Growth and Learning

• Build Open and Honest Relationships with Communication

• Build a Positive Team and Family Spirit

• Do More with Less

• Be Passionate and Determined

• Be Humble