As fireworks explode into overcast skies, I know this is really happening.

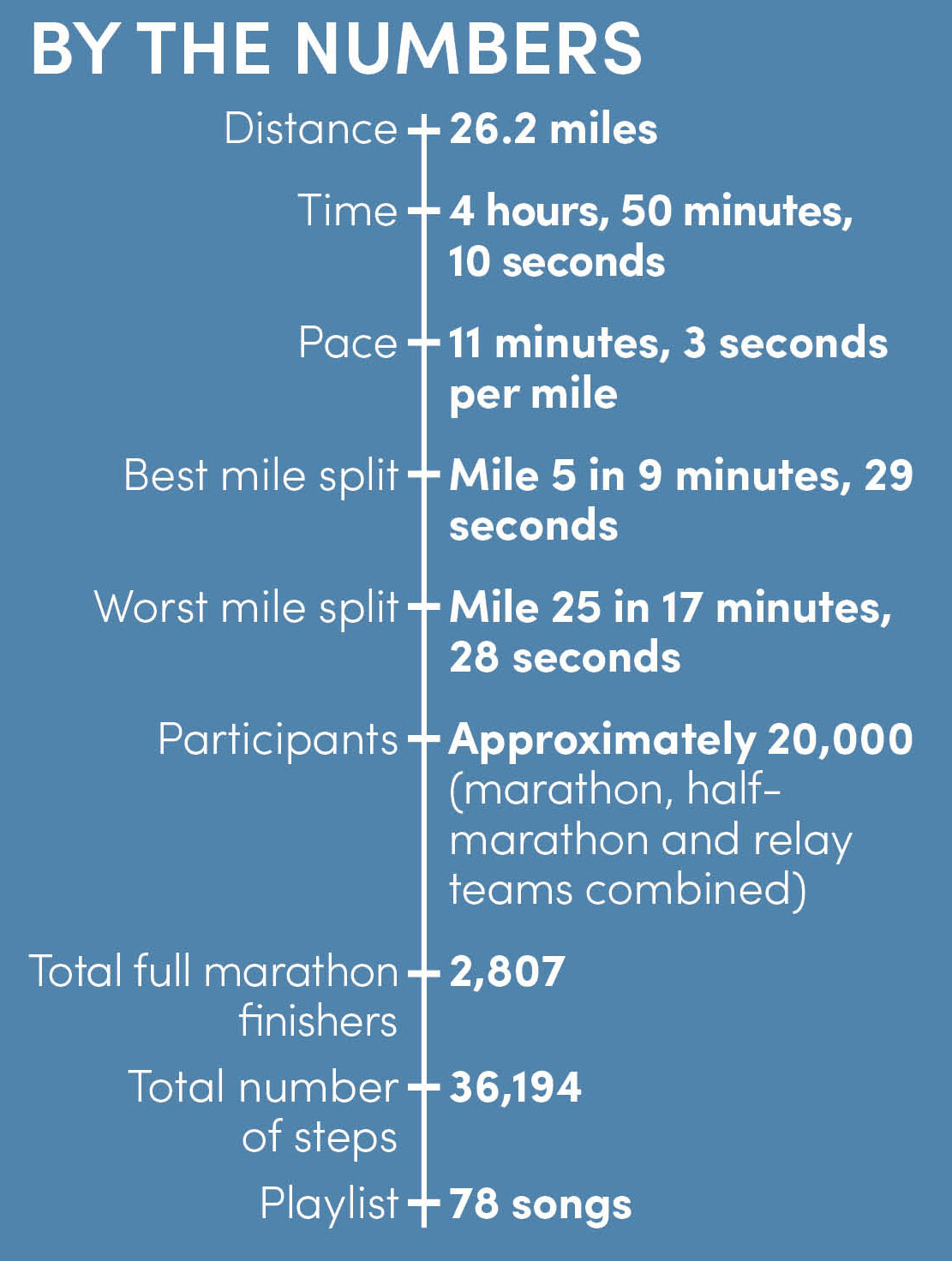

After months of telling people “No, I can’t, I’m training for a marathon,” months of Saturday mornings sacrificed for 12-mile runs, months of constantly refreshing the marathon website for new updates, months of studying the course map, and hundreds of miles of training, I’m here at the corner of Young and Griffin streets in Downtown Dallas. I’m moments away from beginning a 26.2-mile test of my physical limits, my drive, and my mental strength. As I approach the starting line, I press start on my fitness tracker, press play on my five-hour playlist and take the first of about 36,000 steps. And I say goodbye to my aunt and uncle. They’re running today, too, but I plan on finishing before them.

This journey started long before my training for the 46th annual Dallas Marathon. It goes back to a conference room at SUCCESS headquarters in the middle of summer 2015. As a young writer fairly new to the magazine and eager for his first big feature, I volunteered to train for a day with James Lawrence, the man who completed 50 Ironman endurance races in 50 consecutive days in 50 states. I flew to Utah to meet and work out with Lawrence in September 2015 and flew back feeling inspired. Lawrence had never run more than 4 miles at a time until he was 28. If Lawrence, now in his late 30s, could accomplish such a tremendous undertaking, I thought, I could at least start going to the gym more.

Related: The Most Enduring Man in the World

So I did. I signed up for a gym membership and starting working out a few times a week. But I wasn’t satisfied.

I needed something tangible to measure my progress, something that would provide me the sense of accomplishment and validation that I lacked.

My life was fine. I liked my job and my friends and my family. I liked my apartment and my roommate, too. But finally out of school and in the working world, there were no more grades or benchmarks to tell me how I was doing. I needed a challenge. I needed something tangible to measure my progress, something that would provide me the sense of accomplishment and validation that I lacked.

JOHN TOMAC

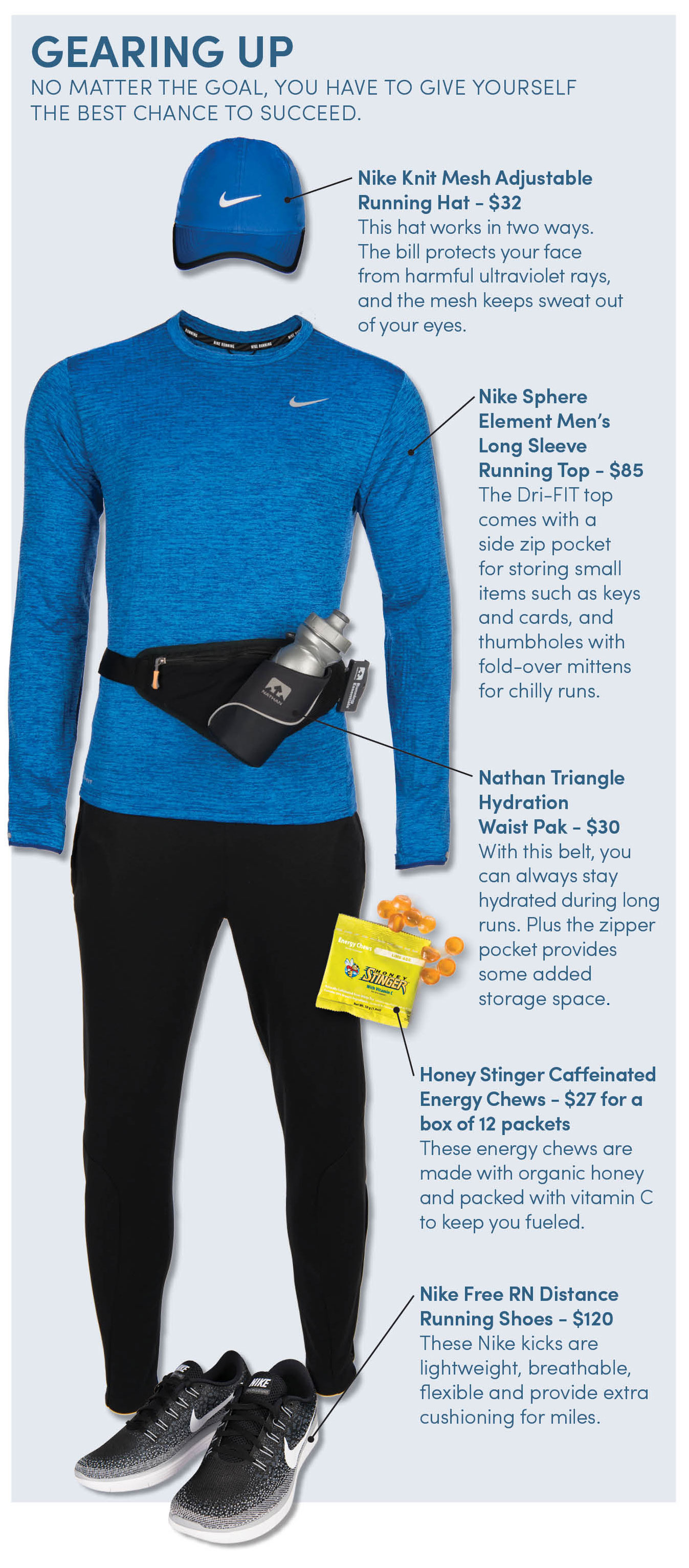

In early 2016 I set a goal to run a 10K by Lent. Running wasn’t new to me. I ran track and cross-country in high school. I was even the captain of the cross-country team—not because I was fast, but because I was a senior and reliable enough to open up the locker room at 6 a.m. every morning. Anyone can run. It doesn’t require fancy equipment, expensive coaching or special talent. So long as you have a decent pair of running shoes and the will to move, you can run. My high school track coach used to tell us: “Running is simply a forward motion—putting one foot in front of the other.”

Miles 1-9: Swift and Manageable

The 10K led to a half-marathon, and the half-marathon led me here: turning left off of Young Street and down César Chávez Boulevard to complete the first mile. Although I know better, I can only hope each mile feels as good as this one—swift and manageable.

A quick confession: I’ve started a lot of things and quit them. When I was in sixth grade, I wanted to play guitar. I imagined myself playing in my favorite bands, rocking out with thousands of screaming fans. But when my parents bought me a guitar and signed me up for lessons, it seemed too hard, and I quit not long after. I’ve regretted it ever since. I have a similar story with learning French. And soccer. And golf. And tennis. These things were lurking in the recesses of my mind when I signed up for the marathon.

JOHN TOMAC

In the past two weeks, I’ve had recurring nightmares about today. (In one dream, I would get lost on the course and run around aimlessly until waking up in a panicked sweat.) Anxious that the weather wouldn’t cooperate, I checked the forecasts at least a dozen times a day. I had an irrational fear that, somehow, before the race, I would suffer an injury that would prevent me from running. My training had gone so well—steady progress, no major setbacks—that I convinced myself something terrible would happen at any moment and derail me. I worried that an entire year of preparation and training would somehow be for naught.

A few days before the race, I told a friend that this marathon was like my World Series. But instead of competing against another team, I’m competing against myself. If I don’t finish, I can’t blame the other team for being better than I am. The only thing that can stop me from finishing is me. But as I turn right onto Main Street, I’m fine. I have no injuries, I know exactly where I’m going, and the weather is perfect. The temperature is just above 50 degrees. Overnight rain left behind cloudy skies, but by the time I hope to cross the finish line, the clouds are expected to clear with temps in the mid-60s.

Feeling relieved, I laugh in my head at all of the things I was nervous about. After all, I’m not the first person to run a marathon. The modern sport was inspired by a Greek courier named Pheidippides, who in 490 B.C. ran about 26 miles from the battle against the Persians at Marathon to Athens to inform his countrymen of their victory. The marathon was one of first modern Olympic events in 1896. Today the best runners in the world are Kenyan, able to finish a marathon in a little more than two hours. Today my goal is simply to finish, preferably under five hours.

Save for a couple of challenging hills, these first few miles roll by easily. I’m cruising through Dallas’s trendiest neighborhoods at a pace that is not only comfortable but also ahead of my goal of 10 minutes, 15 seconds per mile. The beginning of the marathon reminds me of the beginning of my training. Like any new goal, the first few steps feel simple and easy. If you want to learn to play the guitar, you feel a sense of achievement simply because you bought a guitar, signed up for lessons and learned a couple of chords. If your challenge is learning a new language, you show off the simple sentences you’ve picked up.

Early in my training, I found delight every time I crossed off a short run. But as my preparation intensified, those 4-mile runs were soon the “easy” days—a break from the grueling, time-consuming treks that filled most of my days. It’s no different than working toward any big goal. Mastering real guitar riffs is more difficult than learning the strings. Conjugating verbs in different tenses becomes more confusing than speaking in the present. The biggest challenges are still ahead.

“Every big goal is a collection of smaller goals.”

Daniel Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, says that taking pride in those little victories is normal. I spoke to Pink at a point in my training when I was running as many as 40 miles per week. Pink helped me understand how every week of training, no matter how arduous, was preparing me for the next and eventually for the marathon. “Every big goal is a collection of smaller goals,” Pink says. “Most of our experience as human beings is about smaller goals and smaller achievements that might, in the end, result in achieving that big goal.”

Related: 9 Ways to Achieve Your Biggest Goals—Quickly

Miles 10-13.2: Pacing

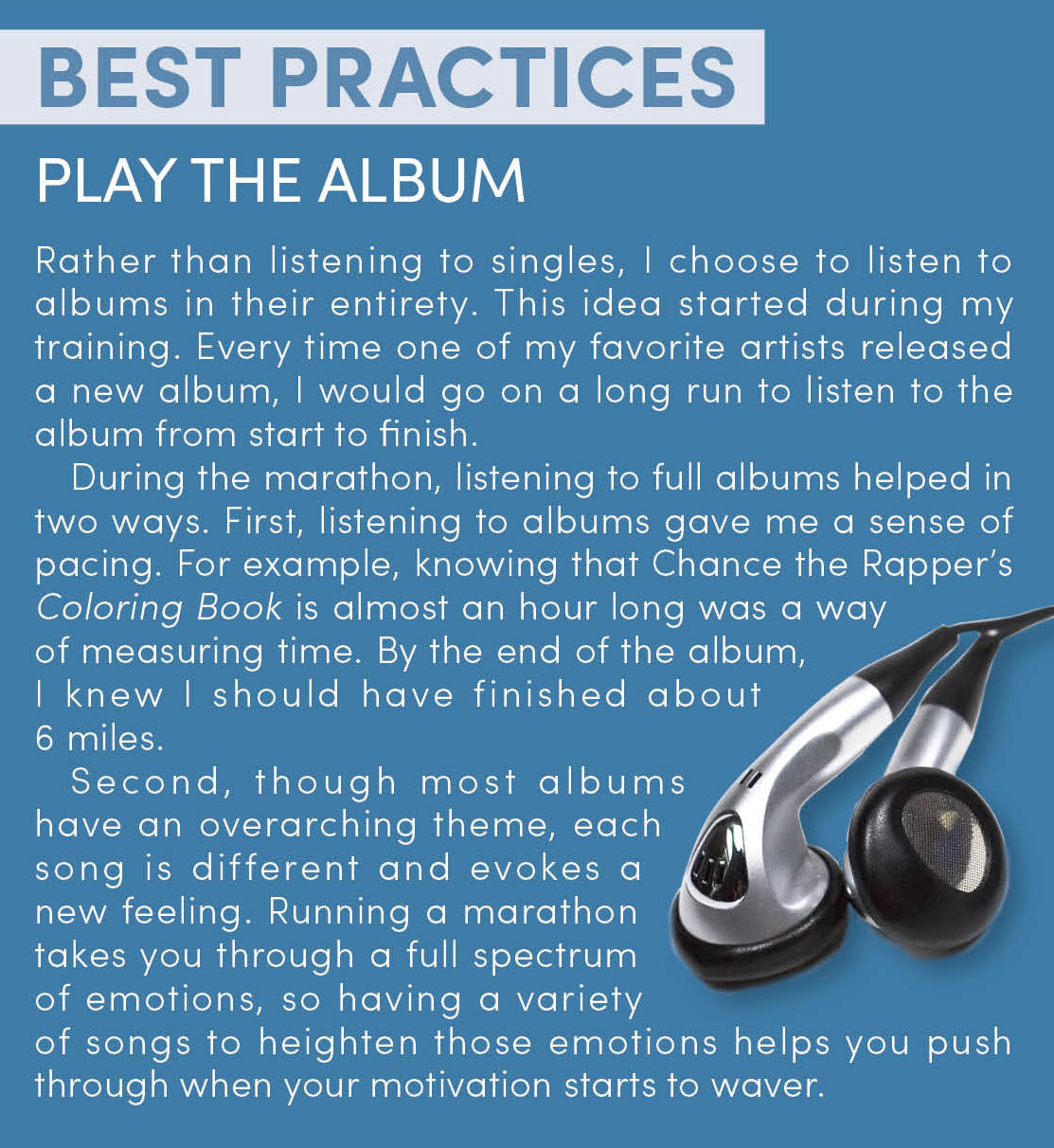

Making my way down Greenville Avenue, I’m at the peak of what is known as the runner’s high: a mental and physical state when the body is producing endorphins, the brain’s “feel-good” chemicals. Faces pass and I don’t even feel as if I’m running. I’m floating as I take in the scenery. I’m mouthing the lyrics to the songs on my playlist and high-fiving spectators whose hands are stretched out. At one point, I run by a photographer, point at the camera and grin.

Nearing Mile 10, those participating in the half-marathon—more than 6,700 runners—veer onto a different course taking them back toward the finish line in downtown, and those of us running the full marathon continue on the longer course in the opposite direction. From the start of the marathon, I was surrounded by people—fellow runners and hundreds of spectators along the course—but now I feel alone. A couple of miles ago, I was within arm’s reach of other runners, and the streets were lined with family and friends who came out to support their loved ones. Now the people closest to me are a few scattered runners 100 yards behind me and a small pack of runners 300 yards ahead.

During these miles approaching the halfway point, I think about the time after I finished my 10K. I was proud of myself, and I would have been content to finish there. In fact, after the 10K, running wasn’t satisfying anymore; there were no more little victories and it felt like the next goal was so far away. This is the moment when a lot of people settle and become complacent. They’re happy knowing how to play a song or two on a guitar they rarely pick up. They’re satisfied knowing how to order dinner in a foreign tongue or building a business that has a slow trickle of profits, enough to live on. Deep down, though, I knew I could push myself to do more, which is why I set a new finish line.

When I ran in the mountains of Utah with Lawrence, he gave me a bit of advice: When you’re running up steep hills, it’s better to walk and conserve your energy. His words run through my mind as I approach the tallest hill of the marathon. During Mile 12, running up White Rock Road, I walk for the first time since the marathon began. I feel slightly disappointed in myself for doing so. It’s too early to walk, I tell myself. But I know I’m being smart. I’ll thank myself later for not sprinting uphill now.

JOHN TOMAC

When I first set this goal for myself, I reached out to Elizabeth Brown, my high school cross-country coach. She, too, warned me to pace myself. “Being your first marathon, it’s going to be an endurance test and a focus on not injuring yourself,” she said. “Don’t get down on yourself if you need to slow down or even walk briefly. Completing it is amazing in itself.”

As my legs thank me for the brief but much-needed rest, her words console me. That comes as something of a surprise because in high school she always wanted me to run faster, not slower.

Miles 13.2-19: No Comfort

After reaching the crest of the hill, I can see my weekend sanctuary: White Rock Lake. In the three months leading up to my race, the lake is where I ran almost every Saturday morning. With a perimeter of just over 9 miles, smooth trails and countless spots for photo opportunities, the lake quickly became one of my favorite places to visit. Every week I looked forward to my long run at the lake. It’s where I pushed myself. It’s where I ran my first half-marathon and every long-distance milestone after that, including a 20-mile run. The lake is where I found comfort. I found peace in the stillness of the water and the greenery that surrounds it. I found solace knowing that I was joined by dozens of runners who, despite being at different points in their training, all came to the lake with a shared purpose: to do something good for their bodies.

Today, though, there’s no peace or comfort here. I’m tired. To make things worse, Mile 15 is where we turn around to head back toward downtown. Now I’m running south and into the wind. My pace slows. The photographers who, not long ago, captured me jubilant and smiling for the cameras, now catch me grimacing and fatigued.

Doubt enters my mind for the first time. The physical discomfort is manageable right now, but I wonder how much harder it’s going to be. I wonder whether it will be too hard.

The nature of mastery is that most of the time you’re doing it, you’re not going to be having fun, and that’s true of most worthwhile endeavors.”

“Achieving mastery is not something that is going to feel good all the time. In fact, it won’t feel good most of the time,” says Pink, the author, who ran his first marathon in 1999. “There’s a certain amount of pain and discomfort attached to that, but that’s how people get better at something. The nature of mastery is that most of the time you’re doing it, you’re not going to be having fun, and that’s true of most worthwhile endeavors.”

Related: If It Doesn’t Suck, It’s Not Worth Doing

I remember that no matter how challenging my runs were while I was training, I always found a way to finish. There were runs in the rain, runs at heat indexes as high as 98 degrees and wind chills as low as 22. On several occasions, I woke up before the sun and ran through darkness to ensure I could fit training, work and a social life into a day. Once I even finished an 18-mile run with a severe upper respiratory infection.

If I could do all of that then, I tell myself, I can do this now.

Miles 20-21: The Rabbit

I say goodbye to the lake and continue down the Santa Fe Trail, an annex of the White Rock Lake Trail. This is where I would run when my training plan called for more than just a 9-mile lap around the lake. I never liked this trail. During my long runs, the scenery here felt so desolate, and the pavement even seemed harder against my legs. That’s how it feels today, too. Although there are a few spectators along the trail, the numbers pale in comparison to the size of the crowds during the first half of the race. And a familiar face in the crowd right now could go a long way. I pull out my phone to see if anyone has texted me words of encouragement.

At Mile 21, I enter uncharted territory. A 20-mile run was the longest of my training. Most marathon training plans suggest running no more than 20 miles at a time because it takes such a toll on the body. Not only is my body starting to wear down, but my mind is, too. I don’t know what to expect from the next 6 miles.

One of my biggest fears in life is failure. Being a people-pleaser, I’m even more terrified of disappointing others. What happens if I can’t finish? I ask myself. Will my loved ones still be proud of me for trying? What good is it to train for an entire year if you can’t finish?

I was warned about the last 6 miles. Hal Higdon is the author of Run Fast: How to Beat Your Best Time Every Time and 10 other books on running. I used Higdon’s training plan to prepare for the marathon. At 85, he has run 111 marathons, with a personal record of 2 hours 21 minutes and 55 seconds, barely 20 minutes off the world-record pace.

Higdon told me that the last 6 miles is where the real challenge begins.

“You probably will suffer as much in the last 6 miles as you will have in the first 20 miles,” Higdon said. “If you pace yourself well, the first 20 miles you’ll be floating along, high-fiving people, enjoying the scenery and talking to people. The last 6 miles won’t be painless.”

I’m afraid I’m about to hit what many marathon runners refer to as The Wall. For some The Wall is physical. Runners reach a point of exhaustion they’ve never felt before. For others The Wall is mental. They begin to doubt their ability to finish. Most runners say they experience The Wall around Mile 22.

“If you have trained well and if you have your nutritional act together, you should be able to sail not over The Wall but through it as though you were Doctor Strange and had magical powers,” Higdon told me.

I’m not Doctor Strange, and The Wall hits me at Mile 21. For me, The Wall is part physical and part mental. It feels like my mind is at war with itself. I want to stop.

But no, I don’t.

Yes, I do.

No, I think I can keep going. I worry my legs might give out. Or maybe I’ll faint.

Running by a school and park, I finally start to walk again. I need a break. My legs have never felt like this before. I’ve never felt so drained. I rationalize, telling myself that a short rest will allow me to finish strong. Walking with my head down and my hands on my hips, I hear a voice yelling behind me. “No walking! C’mon, man. You can do this.”

JOHN TOMAC

I turn around and see that the voice isn’t from a spectator. It’s the 4-hour-45-minute pacesetter. Every marathon has several pacesetters, also referred to as rabbits, whose job is to run at a specific pace to finish in a certain time. I stop walking and run with him. This pace is pretty comfortable, and I think I can keep up with him. I feel renewed.

I can do this.

Miles 22-25: Pain and Grit

Running down a street—who even knows which street at this point—next to the pacesetter, other runners and dozens of spectators, I start crying. At first it’s surprising. I had never cried during a run, although there were some tears after I completed my first half-marathon. But it occurs to me that I’m crying because I’ve accomplished something. I’ve completed 21 miles, and I have only five left. Tears stream down my face because I’m proud of what I’ve done up to this point: not only did I train hard to be here, but I’m almost done. I also cry because I accept that this “wall” can’t control me. This wall won’t stop me from finishing. I didn’t train so hard so I could quit with 5 miles left. At this point, it’s only a matter of time. Sniffling a bit in the wind, I tell myself, There is no such thing as a wall.

This feeling of empowerment doesn’t last long, though. I can’t keep up the pace and fall behind the pack of runners who had joined the pacesetter. I’m OK with this. I know I can finish. As I make my way toward downtown, the road feels just as lonely as it did a few hours ago. Only this time I actually prefer it this way.

During Mile 23, an excruciating pain shoots up from my ankle. The pain is so unbearable that it forces me to stop, and I walk over to a curb to examine my injury. I can’t figure out what’s wrong, so I do some light stretching and start walking. I tell myself that I didn’t train so hard for an ankle injury to keep me from finishing. I keep running. (After the race, I’ll have X-rays on my foot to make sure it’s not a stress fracture. Thankfully, it wasn’t.)

At Mile 24, I stop again. I’ve never felt pain like this before. Everything hurts—my knees, my thighs, my calves, my ankles, my back, my feet. I’m going through the catalog of aching body parts and decide every part hurts. But I can see the Dallas skyline, and I know I’m close. Again, I tell myself that I didn’t train so hard just to wear out with 2 miles left.

Lauren Eskreis-Winkler, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania who has co-authored work with Angela Duckworth (Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance), says having a purpose—along with deliberate practice, interest and hope—is a key to developing the fortitude it takes to accomplish a goal.

Related: 10 Steps to Achieve Any Goal

“Most people, when they have an abiding passion or something they’re gritty about, the way they frame it is that they do it for the benefit of others,” Winkler told me before the marathon. “Even for pursuits that seem incredibly self-centered, people frame it in terms of a broader goal that has an impact beyond themselves.”

Before my race, coach Brown suggested I make a list of 26 people and that I think of one person for every mile. I didn’t make a list, but as I fight through this mile, I think of everyone waiting for me at the finish line: my parents; my brother Danny; my aunt Melissa; my cousins Damon and Roberto; and my friends Kyle, Moe, Marina, Marco and Nick. I think about those whom I’ve already seen today, my boss and his girlfriend, and everyone who has texted me during the marathon.

They’re waiting for me.

Although running a marathon is a selfish goal, I hoped that through my selfishness I would inspire others, and I have. Before the marathon, my roommate decided he wants to run a half-marathon with me. My mom wants to start running. My entire family wants to participate in Dallas’s 2017 Turkey Trot 5K. I can’t let them down. I’m getting that medal today.

I grit my teeth and push myself.

Mile 26 to 26.2 and Beyond: Unfinished

Chance the Rapper’s “Sunday Candy” blasts through my headphones as I near the end of Mile 26. My Sunday Candy today is the finisher medal, and I want that medal. I see a sign that says “Final 800 meters,” and I receive my final wind of energy and a wave of fervor. This isn’t those guitar lessons or those French classes.

During my training I ran hundreds of miles. In the last month before the marathon, I ran more than 133 miles. Today I’ve run 26 miles. What’s 800 meters more? Eight hundred more and you’re done. As soon as I run past the sign, I enter a full sprint. I remember a technique I learned in cross-country, and I start picking people off one by one as I near the finish line. I run with every last ounce of energy my body has in me. If I collapse at the finish line because I ran too hard, so be it. I want to leave it all out here. I run so fast I don’t even see my friends and family on the sidewalk. I run harder and faster and stronger than I ever have before. I step across the finish and throw my hands up in the air.

After running for 4 hours, 50 minutes and 10 seconds, I’m done. I finished. I did it. It’s over.

The finish line is more anticlimactic than I had imagined, though. In the months leading up to today, every time I pictured myself finishing I thought I would cry. I would even tear up just thinking about how much I thought I would cry. But I don’t cry. A marathon volunteer places the finisher medal around my neck. I grab a bottle of water and look for my family. All I want is to sit. I had planned on going out for drinks with my friends to celebrate, but I don’t want drinks. I want to go home, take my shoes off, sit on my couch and not move for a very long time.

Later that night, I join my family for a big celebration. My aunt and uncle had also completed the marathon, and we all feast over wings, burgers and beer. Although we’re celebrating our accomplishment, I don’t feel accomplished. I don’t feel as if I just achieved what I’d been training for all year. I thought I would be overwhelmed with joy and pride for finishing, but I’m not.

In the days that follow, that rewarding feeling of validation I sought for so long never comes. Although I’m proud of myself, I’m not satisfied. I want to achieve more because I realize that although I crossed a literal finish line, there’s always something more—just as my first goal to work out more led me to run a 10K, which led to a half-marathon which led me to run this marathon. The marathon finish line on Young Street was really a starting line for more. The pleasure, it turns out, came from the work I put in, not the results.

Setting new goals and constantly challenging ourselves is how we grow; it’s how we keep from becoming complacent, and it’s what makes life fun.

Just four days afterward, I’m still recovering from the damage a marathon does to the body: sore quads, an aching back, random muscle spasms shooting through my entire body. From my couch, I tally likes on pictures of the marathon on Facebook and review my mile splits for the hundredth time, and I think about James Lawrence and his 50 marathons in 50 days. I flirt with the idea of running 50 marathons by the time I turn 50—essentially two a year for the next 25 years of my life. After thinking about the whole ordeal, from conception to completion, I realize that merely finishing was never the real goal. I relished the challenge, the chance to push myself. Setting new goals and constantly challenging ourselves is how we grow; it’s how we keep from becoming complacent, and it’s what makes life fun.

So I’ll run another marathon and then another one, and I’ll keep running until maybe one day I’ll feel as if I’ve reached a finish line. Maybe I’ll never reach that finish line—that feeling of satisfaction—but I least I’ll be able to say I tried. In the meantime, I might see if I can find that old guitar.

Related: 5 Things Jogging Taught Me About Success

This article originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of SUCCESS magazine.