I’ll be honest. I wasn’t sure what to expect when I sat down for my interview with Payal Kadakia.

I knew she had recently had a baby and that the interview shifted a few times to accommodate the baby’s nap schedule. (This didn’t bother me. I have two kids of my own and know how sacred those naps are.) I also knew that she was the creator and founder of ClassPass, a company that takes all the disparate fitness studio classes in any given area and organizes them to be booked through one central place. Over the course of the last decade, Kadakia and her team executed through setbacks and successes to create a company valued at over $1 billion in its latest round of funding, back in January.

But “back in January,” is an interesting phrase when referring to January 2020. Which is why, when I sat down in the makeshift studio I’d built in my NYC closet to interview Kadakia via Zoom during quarantine, I wasn’t sure what to expect. A global pandemic had just upended the entire group fitness industry, ClassPass with it. If I, myself, was going a little crazy wanting to get back to my spin classes, how must Kadakia feel? Her business depended on it.

Within the first few sentences, it was clear who I was talking to. Kadakia was calm, confident and clearly up for the challenge of change. The truth is that no entrepreneur gets her company to a 10-figure valuation with a short, simple, easy story. The actual route was long and winding, filled with pivots and switchbacks and went all the way back to Kadakia’s childhood. If ClassPass and the industry it supports are going to thrive again, Kadakia’s backstory will have everything to do with the happy conclusion.

Short Story

Yes, Kadakia did come up with a great idea. When and where are no secret in ClassPass lore. It was 2010. She was 27, still at the Warner Music Group offices, sitting at her desk after the workday had ended, somewhere between mentally fatigued and emotionally restless. A pair of ballet shoes were in a bag under her desk, waiting. And she was desperate to use them. Dance was Kadakia’s joy, her passion, her escape, the thing that made her whole.

All she had to do was find a dance class, but it proved more complicated than she’d hoped. She couldn’t find the right class at the right time and was navigating so many websites.

“Two hours go by and I look at the clock and think, “Oh my God, all these classes are over because I’ve wasted all this time looking at the screen,’ ” she recalls.

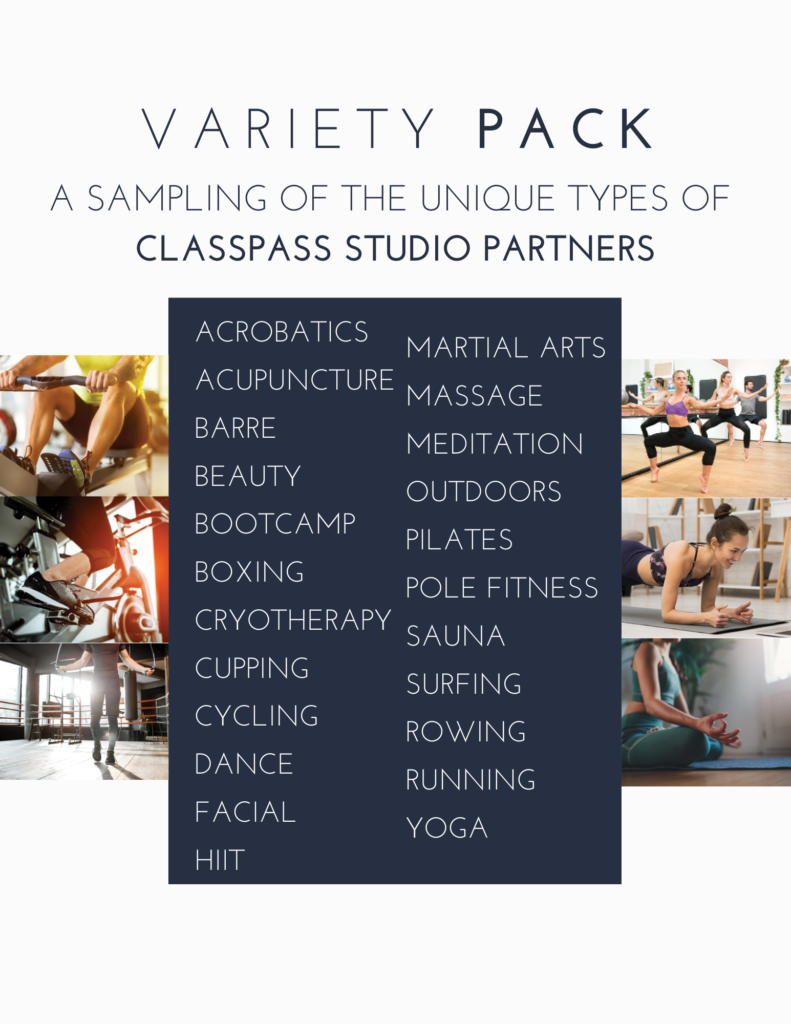

So, again, that was the moment, and ClassPass was the great idea: one membership that provides access to a vast array of unique fitness studios and gyms specializing in everything from dance, to boxing, to outdoor bootcamps, to yoga, and on and on.

Do you really need to know more?

With entrepreneurial success stories, the tendency is to focus on what exists between idea and execution. But ideas rarely occur in one moment and the ability to execute is something that is often developed, sometimes intentionally and other times quietly in the background, over a lifetime. Spend a little while with Kadakia, and you’ll realize that the idea didn’t actually start that night at her desk as she searched for a ballet class in the city.

That moment is certainly a key turning point and Kadakia has told the story in various interviews, but if you consider that evening a little further you could come up with a few more questions. Was she simply restless from a long workday, or being pulled by something else? Why ballet shoes? Warner Music Group was the second big company she worked for out of college, did she realize that the wheels had already been in motion for it to be her last?

There is always a long version of any short story. And when it comes to Payal Kadakia, that happens to be the best part.

Long Story

Dance was Kadakia’s first love. The daughter of Indian immigrants, Kadakia grew up in a New Jersey neighborhood where no one looked quite like her family. She was aware she was different, and if she happened to forget, there was often a mean-spirited kid around to remind her. It was only when she was introduced to Indian dance that she remembers embracing an aspect of her heritage and making it her own.

“When I was younger, being Indian was a big part of my life,” she says. “It’s what made me feel different in a good way and a bad way. It was my strength when it came to dance, but it was also something I was made fun of for.”

But Indian dance isn’t quite as ubiquitous in New Jersey (or the United States) as plenty of other extracurricular youth activities. There were no organized classes like she might find for, say, cheerleading, or ballet or tennis. Like many immigrants, Kadakia’s parents managed to find their community among other Indian families in the neighboring area.

Usha Patel, a close friend of her mother, had studied at some of the most prestigious performing arts schools in India. When Kadakia was just 3, Patel began to teach her traditional Indian dance. As Kadakia grew up, she watched Bollywood films and became enchanted with the glamorous ways the form was incorporated onto the screen.

Soon, Patel (Kadakia still calls her “my Usha Auntie”) welcomed other children looking for a creative outlet. “I think what I really loved about it when I was younger was the sense of community and the sense of friends,” Kadakia says. Indian dance is a beautiful form of artistic expression—it draws on a tradition of storytelling that emotes feelings and narratives through movement and vivid facial expressions—but Kadakia’s training didn’t exactly occur in the most glamorous of environments. Most of her lessons occurred in various basements. “It was all very makeshift.”

Yet there was something special about the informality of what happened in those basements; a safe and sacred place not only to express yourself, but to simply be yourself. Often, these safe and sacred places are found by accident; it’s hard to plan the kind of magic that happened there. Kadakia was lucky to have found it in the first place. Another child might have never had that opportunity. Another child of immigrants could have longed for this type of community and identity, but sadly never found their basements. Conversely, Americans with no Indian background might have appreciated and wanted to participate in the art form, but because it was highly unlikely to stumble into a basement, the lack of visibility and availability made it inaccessible.

“You would have had to have known your own ‘Usha Auntie’ through a friend. It was all word of mouth,” she says.

Of course, Kadakia was just a kid when all this was happening. She wasn’t overtly asking herself the big What If questions that lead to billion-dollar companies. But people tend to remember things. Otherwise, where would their ideas come from?

* * *

Everyone is always waiting around for inspiration to strike, but executing an idea is the product of what you did in the time you were waiting for that idea to come along. Did you develop skills, characteristics, and knowledge so when the idea finally came along, you could execute it?

When Kadakia wasn’t in the basement of a family friend or on a makeshift stage, she was overachieving. She excelled in math and science, becoming the first girl at her high school to win a physics award. She attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Success was laid out in front of her as a series of extremely difficult but achievable goals, and hard work and discipline were what it took to accomplish them.

After college she landed a job at Bain & Company, a management consulting firm, where she quickly earned the nickname “the queen of cold calling.” She was a fast riser with an extremely bright future.

And yet dance only became a bigger and bigger part of her life. It was her respite from the expectations placed on her by herself and others, and it was crammed into every spare moment she could manage. If she wasn’t at work, she was on a dance stage or preparing to be on one.

In 2008 Kadakia founded the Sa Dance Company, providing a more professional stage for Indian dancers who may have been relegated as accessories to things like weddings or other events. The side hustle made it clear that there was a distinct line between the life she wanted to live and the path she was told defined success.

“I was living two identities,” she says. “I had this job that I went to that I wasn’t excited about. Then at night I was this dancer, entrepreneur, creative person. It felt like I was two different people.”

Neither of those identities knew anything about the idea that hadn’t even formed yet. But she built them both up with an intensity that not only required creativity and skill but developed them in her. That is until they both grew so large they couldn’t reasonably coexist in any one person’s schedule.

* * *

Kadakia’s move from Bain & Company to Warner Music Group likely appeared to the outside world as simply a sought-after employee pivoting from one great opportunity to another. But while she was barely willing to admit it to herself, it was a big step from one identity into another.

For most of her life, Kadakia had been more or less pleasing her parents and the various people who saw her potential and projected outlets for it. “I don’t know if my [career plans] were my goals or if they were society’s goals,” she says.

Kadakia’s position at Bain & Company often required last-minute travel and spontaneous client meetings after typical work hours. But her new job at Warner Music Group offered something invaluable at that moment: predictability with her schedule.

“That was the first time I said that I was going to start setting goals on both sides,” Kadakia remembers. For the next few years she held a position at Warner while Sa Dance began to garner positive critical attention around New York City. “I learned a lot in that two and a half years where I feel like I started to bet on myself,” she says. “I started saying, ‘If I really was in control of my career and my time and I let my passions guide me, what could I do?’ ”

And that’s how we arrive at the big moment in 2010 when she had those ballet shoes in her bag. (In addition to traditional Indian dance forms, Sa’s movements are inspired by ballet, jazz and hip-hop.)

As we know, she missed that ballet class. It was just a microcosm of an issue that she’d been working her way around since her youth: a lack of simple availability to participate. The inability to “find the basements” where people gathered to share in an art form. She was well-attuned to the problem. Her background just happened to make her tailor-made to find a solution.

* * *

Ideas don’t go away so easily when they resonate with different parts of your past. That moment in 2010 produced a specific thought: “I realized that if I wanted to help people stay passionate and stay connected to their hobbies and things they love, I needed to build a website,” Kadakia says.

For months, she and co-founder Sanjiv Sanghavi researched, planned, and set up the conditions to create what would eventually become ClassPass. But in order for that reality to ever take form, there were two difficult internal steps for Kadakia to confront: She would have to quit her safe, secure full-time job, and almost as tough for her personally, she would have to tell her parents she was quitting that safe, secure full-time job.

Kadakia’s mother and father had motivated and driven her to accomplish all she had. They instilled in her the qualities that led to such a great job. It was over Thanksgiving weekend that she told them that she didn’t want to be at the job that took care of her financially. She wanted to make her biggest pivot yet.

One might have expected them to tell her leaving was too risky. She certainly expected that. Heck, they might have expected themselves to tell her that. But she had met every goal placed in front of her to that point, so they knew what she was capable of. And while she hadn’t fully decided yet to build her company, when Kadakia told her parents she simply didn’t want to go back to work on Monday, her mother looked at her and, to everyone’s surprise, told her to quit.

“She said, ‘I believe in you. This is the time if you’re going to do it. Go bet on yourself and build something.’ ”

And she did.

Kadakia knew how to solve problems and how to weather small disappointments. A woman and a minority, she didn’t seem fazed when navigating the overwhelmingly white male world of venture capital, and eventually made a habit of wearing Lululemon leggings to some of her biggest meetings. After officially launching in 2013, ClassPass went through two major business model pivots on its road to prominence. Along the way, Sanghavi left his operational role in the company, and in 2017 Kadakia stepped into the vision-focused position of chairman and turned the day-to-day business over to CEO Fritz Lanman. And as ClassPass started to become the company that would eventually be worth over $1 billion, Kadakia began to settle into her real self.

“Wanting ClassPass to succeed came from a visceral mission I had as opposed to, ‘Oh, my dad wants me to have this job,’ which is a very different reason to show up,” she says. “I think that same creativity and the same feeling that I was getting from dancing came out when I went to work on ClassPass.”

She was no longer living two identities. She was working tirelessly, but some semblance of life balance began to fall into place. In 2016, after a little over two years of dating, she married lawyer Nick Pujji. And earlier in 2020, she gave birth to their first child, a son, Zayn—the aforementioned napper. By so many measures, it would seem to be the perfect fairy tale ending to the long version of the ClassPass-Kadakia tale.

Except…

Long Story Longer

By the time COVID-19 hit the U.S. this past winter, ClassPass had grown to more than 700 employees while expanding to 30 countries across five continents.

It’s no surprise, of course, that a business built on its ability to connect mostly metropolitan customers to in-person workouts would be adversely affected by the halting of in-person anything. Kadakia shares that ClassPass lost roughly 95 percent of its revenue in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic gripping the U.S. According to a CNBC report, it was forced to lay off some 22 percent of its staff and furlough another 31 percent as business dipped.

The company still counts almost a million members, with more than 2,000 corporate and enterprise clients. ClassPass is not unlike other tech platforms such as Airbnb and Uber that help connect demand to unmet supply. And just as those companies have taken their share of criticism from hosts and drivers for a variety of reasons, ClassPass has received complaints from some of the studios with which it has partnered.

A Vice report in February, before the realities of the pandemic set in, aired concerns from 18 ClassPass partner studios distressing over the controlling effects of the platform on their businesses. In the article, a ClassPass spokesperson pointed out that the complaints came from a small minority of the company’s more than 30,000 partners around the world.

There would be no ClassPass, obviously, if there were no Pilates studios or spin classes. As social distancing protocols and shutdowns hit the world, ClassPass quickly revised its model to serve both customers and partners—the kind of pivot the business might not be so prepared to make were it not already an important part of its origin story and its founder’s background.

“One of the things we have to focus on during this time is keeping our partners afloat,” Kadakia says. “So we’ve done a few things. We did a partner donation fund where customers can donate to their studios…. We flipped our entire product for on-demand video and livestream video.” ClassPass also waived all commission, sending digital revenue directly back to studios from March through August.

ClassPass now offers 50,000 on-demand and livestream digital classes a week for its customers to exercise at home while still supporting studio owners.

“We know it’s not the same experience as going in person, and we can’t wait for people to do that again, but that’s what we had to do,” Kadakia says. “We still have the same mission—getting people to move, to be passionate about working out. That doesn’t change.

“What I keep telling my team, what I keep reminding other people is this is a great moment to go back to your True North.”

Like many businesses that have not been able to survive through the harsh realities of the pandemic, some ClassPass partners have gone under. Can ClassPass itself survive, keeping as many partners as possible in business at the same time?

That part remains to be seen—just as no one could’ve predicted COVID-19, no one can predict the future business realities it will create.

But it’s worth noting that, like all great stories, this one comes full circle. Through ClassPass’s most recent pivot to bring the fitness studio experience in-home, through streaming video, Kadakia and her team have created that safe and sacred place where its customers can not only express themselves, but simply be themselves through all forms of physical movement. Some people have home gyms where they’re completing these workouts, while others are conducting them in their living rooms or other open spaces. And many of the people streaming those fitness classes across the globe, go figure, are working out in their basements.

Is all this change and uncertainty uncomfortable? Most definitely. But once again, Kadakia draws her strength from a lifetime of experience.

“I always think back to the day I mustered up the courage to quit my job, a very hard thing for anyone to do,” she says. “That day created a shift in the way I think about and approach fear or blocks in my life forever. I remember thinking to myself, I walked to work today with so much fear and I walked out with the door wide open.

“Now whenever I’m faced with fear or challenges, I think back to that day and remember that, as hard as the door is to open, there is always more on the other side.”

READY FOR CHANGE?

Payal Kadakia left a great job to build ClassPass. but it wasn’t an easy decision, and it definitely wasn’t spontaneous.

Consider her experience and words if you’re mulling the same kind of entrepreneurial decision for yourself.

Know why:

“What comes to mind is having a mission. What made me so excited about [starting ClassPass] was helping people have what I had with dance in my life, but in their lives.”

Be financially stable:

“I had three years of savings that I knew I could use to get through building

the company.”

Set a personal budget:

Others invested in the company, but Kadakia’s savings had to support her.

“My dad and I sat down and came up with a budget. I could live off what I had saved.”

Summon all your attention:

“It’s a baby. It needs your full attention and 100 percent of your time.”

Understand your ceiling:

“Is this a big enough idea for me to quit my job over?”

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2020 issue of SUCCESS magazine.

Photos by © Christopher Patey