In the summer between middle and high school, I spent an afternoon in the window of our family’s seafront budget-friendly room watching an artist sculpt a giant Jesus in the sand. We were on vacation in Ocean City, Maryland, the noisy little strand along the Atlantic Ocean where we went every summer. This year was different. On the advice of a family friend, we stayed at the Plim Plaza hotel. It was right on the boardwalk and quite a departure from the quaint bayside inn where we’d spent three or four nights every July before this one. The Plim Plaza was an OK hotel, I suppose, if not for a slow elevator, small rooms, a lack of private balconies, and the fact that my father kept calling it a dump. These all were cosmetic problems compared to the real trouble hanging over the trip: the indisputable fact that I was 13.

Their names were Annie and Kelli, smart and funny and pretty classmates who’d only recently started to invite me to the cool kids’ eighth-grade parties. These gatherings were stressful affairs in which I rarely spoke, dodged games of spin the bottle, and watched Faces of Death VHS tapes that kept me awake for weeks. But being a part of them somehow felt like the key to a better future. At some point that summer, the three of us learned that our family vacations to Ocean City would overlap and we agreed to meet. This was 1993, though, somewhere in between Prodigy and Netscape Navigator in technology years, so hotel-to-hotel calls were our only method of communication. Annie and Kelli left the arrangements in a message on our touch-tone room phone one morning: The plan was that they’d walk down the boardwalk at some point that afternoon and wave at me to come down.

I went to the window at exactly noon and waited for “some point that afternoon” to arrive. My brother, Kenny, two years younger and with no use for girls at the time, came in and out of the room for drink boxes and bathroom breaks, hauling his boogie board and wondering why I couldn’t ride waves with him. “They’re the big ones,” he said, hoping to cure me of the teenage condition.

PAUL ROGERS

My ailments were much larger than the ocean. I was a skinny first-year teenager with a wardrobe of loose-fitting T-shirts and baggy jean shorts, and a bowl haircut that wrapped from ear to ear. Kenny went off and rode the big ones while I perched in that window, watching people on the boardwalk stroll past the man sculpting the savior.

It’s not a stretch to say that a 13-year-old in 1993 was one of the most uncomfortable living beings in modern history. Hear me out: I was born in 1979, squarely in the middle of the four-year period between 1977 and 1981, putting me at the center of a weird group of about 20 million Americans lost between Generation X and the almighty millennials. We are defined by our lack of definition. We don’t make sense. As we’ve grown up, we’re cynical yet hopeful; loners who believe in being parts of a community; aware that popularity leads to success, but rejecting the sameness of the internet age—an age that took off, by the way, the year we were 13.

Now consider this: I was raised in Maryland, a state that isn’t really Northern and isn’t really Southern, a state next to the nation’s capital, where people make a living flip-flopping. There’s a reason Marylanders boast about their state flag and crabs—these things give us some semblance of an identity.

Also consider that I grew up in a rural area of this in-between state, in a house on a dirt road about a mile back in the woods. We were about 15 minutes from the closest grocery store but only 35 miles from the White House in the center of one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world.

What I’m saying is that you’ve been fairly warned that this is the story of the most awkward afternoon from the most awkward year in the life of the most awkward boy from the most awkward place and the most awkward generation, and if you choose to read on, you run the risk of learning that we’re not all that different.

***

The Ocean City boardwalk was our family’s summer landing strip. Every year, we rolled over the Route 50 drawbridge and onto the busy island in Mom’s silver Chevrolet Celebrity, which had a tape player that was licensed to play only Rod Stewart cassettes and the Dirty Dancing soundtrack over and over. It was the time of our lives.

Related: 17 Quotes About Living a Beautiful Life

As we crossed the bridge, to our left we could see the go-kart tracks and mini-golf courses we’d dreamed of all year, and to the right were a pair of tall waterslides that went straight down and the Tidal Wave roller coaster, which went upside down three times going forward and upside down again three times going backward, which means it went upside down six times.

Just to the right of the drawbridge was Talbot Street Pier, the bayside motel where we stayed in my earliest years. For $69 a night, we got two double beds, a small fridge, a clean bathroom, unlimited access to the cigarette and gumball machines in the lobby, and a private balcony that overlooked a pier filled with charter boats where I met my first dead shark. Downstairs was a bar called M.R. Ducks, which sold M.R. Ducks T-shirts, which were in every Marylander’s closet. Dad had one with a breast pocket for his Winston Lights.

The years at Talbot Street, to my memory, were better than all of the other years. Dad would always take a day to himself and go deep-sea fishing. On the other days, he went to the beach with us and filled buckets with surf-water and sand and dumped them on our heads. At nights, we went to the Trimper’s amusement park, where I rode my first Tilt-A-Whirl. Most of the kiddie rides in the park had horns similar to that of an old Model T horn. As the sun set on these summer nights in Ocean City, the park sounded like the scene of a mass duck slaughter, but to me it still brings back the most pleasant memories.

At night on Talbot Street, we sat in plastic chairs on our third-floor balcony. We rested our drinks on the backside of a humming window-unit air conditioner while we watched the bar crowd come and go below us. Here we could hear the nylon boat ropes strain and slacken, the ding-ding-ding of the drawbridge opening, and the captains honking thank you as they passed through. Kenny and I went to bed early in those years, falling asleep listening to our parents talk outside the window.

One year when I was maybe 6, I woke up to a Smokey the Bear infomercial about preventing forest fires. For some reason I remember this as the first moment in my life when I gave any serious thought to the idea of death. A vacation is quite a time for your mind to reach for the end of infinity. I opened the balcony door crying and tried to explain what Smokey had done. Dad scooped me up. “You don’t have to worry about dying for a long time,” he said. “Just look at all the people at the bar. Look at the pretty girls, Mike.”

PAUL ROGERS

“Oh, Freddie! Stop,” Mom huffed.

“What?” he laughed. “It’s fine.”

I hopped down and stuck my face through the railing and squeaked out a hello to the young women. When they looked up and waved back, I giggled and felt better about the future.

***

Now here I was again, older and with that bowl haircut in our very different hotel, waiting for another wave from girls.

I flipped between MTV and VH1 during a strange summer in music. “I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)” dominated both stations, four years after The Proclaimers released it. UB40’s cover of Elvis’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love with You” also received a good bit of attention, in no small part because one version of the video included clips of Sharon Stone and Billy Baldwin tearing each other’s clothes off in the movie Sliver.

Hours passed. Outside the window the sand kept changing. The artist was creating an image of the crucifixion with a message beside it to let me know that Jesus died for me—a hormonal teenage boy who was quietly ruining his family’s vacation.

The artist, Randy Hofman, started creating sand sculptures at that spot on Second Street in the early 1980s. Whenever rain or wind eroded his work, Hofman brought the Lord to life again. I’m sure some people find meaning in that, but to a teenage boy the sand sculptures had the same effect as Smokey the Bear. So I sat in that window, Sharon Stone inside and Sand Jesus outside, pondering sex and the afterlife.

Look, I told myself, You’ve kissed a girl before. Remember that time with [name redacted to protect her from humiliation] in the elevator at school? Oh yeah, that happened. For every memory like that, though, there was another of me sitting by myself at middle-school dances, nervously sipping soda to keep my hands busy while everyone else danced. I’d smile whenever a teacher walked by to ask how I was doing, because if there’s anything worse than being awkward it’s admitting to an old person that you don’t know how to jump around, jump around, jump up, jump up and get down.

Related: 12 Confidence-Boosting Songs to Pump You Up

Religion was an equally complicated matter. My father was never a believer. When he was 13 or 14, he and some friends were in a classroom at Mackin Catholic School—an all-boys high school in Washington in the 1950s—when they saw prostitutes standing on the corner of 14th and V Streets. The boys all went to the window. The Catholic brother in charge of the class got mad and smacked my father on the back of the leg with a tassel, so Dad turned around and punched the guy and got himself expelled.

I remained hopeful as I sat in the window that at some point I would get to second base and go to heaven.

Still, despite my failings at middle school dances and being the son of man who hurled a fist at a man of the Lord, I remained hopeful as I sat in the window that at some point I would get to second base and go to heaven.

This is the great power of Ocean City. It’s a place where the smell of vinegar from Thrasher’s French Fries or the sight of the giant Ferris wheel or the cha-chunk cha-chunk cha-chunk of tickets spitting out of Skee-Ball machines will light nostalgic memories in anybody who’s been there before. But it’s still a vacation destination, and vacation destinations by definition should make you feel better than you do back there, wherever there is, be it a spot on a map or a point in time you want to forget. These are places that sell the restorative power of faith and hope, heavily marketed stretches of sand that appeal to the American optimist. They’re places that make a 13-year-old boy believe he might get lucky one day and when he does the bells will ring and all the lights in the arcade will flash at once.

Or something like that.

***

“You’re gonna waste your vacation sitting inside, boy,” my father interrupted with the turn of a key. “Your brother’s been out there in the water all day.”

“I’m waiting on my friends, Dad.”

“Well,” he said, “where are they?”

The afternoon slipped away, and sunburned people made their way off the beach. Mom and Dad and Kenny came back and started to take showers and talk about what we’d eat.

In the downstairs of our hotel was a restaurant named Paul Revere Smorgasbord. Propeller planes pulled signs behind their tails that advertised the smorgasbord’s $6.99 all-you-can-eat buffet. If you think about it, Paul Revere is an odd name to put on a restaurant in a city that sells happy memories and the prospect of good news ahead, but I do remember the place offered Jell-O at the end of the buffet line. Who doesn’t look forward to going back to that?

Dinner in Ocean City was my father’s comedy stage. The joke was the same every year, at every restaurant. Whenever a young waitress approached the table, Dad did his best to embarrass me and Kenny. “Can I introduce you to my son? He’s shy,” he’d say.

I’d turn red and wonder what it was like to have a normal father, but now I understand his lesson.

“You need to stop caring so much about what people think,” he’d say.

Related: 12 Things Truly Confident People Do Differently

So this year, in the Plim Plaza window, I decided I would do just that.

“I’m gonna stay here,” I told them of my dinner plans, “and wait for my friends.”

“Like hell you are,” my father said.

It was then, or sometime not long after then, that I looked out the window and saw them. Kelli had flat, dark hair and Annie had dirty-blonde bangs, and there they were! Kelli looked up and tilted her head as she waved one of those joking waves, pretending she was a queen in a parade. She was so funny! She also had a curious look on her face, probably because I was sitting in the window and we didn’t have a balcony, but that’s OK, I told myself, because as soon as I got downstairs, I’d explain that we didn’t usually stay here and that we didn’t know about the slow elevator or the small rooms or the lack of balconies or that the place was a dump, and yes, I’d tell them all of this as we walked up and down the boardwalk all night! I said goodbye to my family and opened the door and bypassed the elevator and ran down the stairs and through the lobby and then, when I got to the glass door that opened to the steps to the boardwalk, I stopped.

Be cool, I told myself.

I walked out the door nonchalantly.

“Hey,” I said to them.

“Were you just sitting in that window all day?” Kelli asked.

No, no, definitely not. What loser would do that?

“Nah, not really.”

They’re looking up at the room. Oh, no! What are they looking at? Oh, no, what are they waving at?

“Is that your dad?”

I stared at Sand Jesus and wished they were talking about another father in another window. I guess some prayers go unanswered, because when I turned around there was my old man, grinning goofily with his mouth closed and head tilted to the side.

In that moment I not only abandoned any hope of being more than friends with either of these girls, I started getting nostalgic for those nightmarish Faces of Death movies, knowing I’d seen my last party with cool kids.

I turned to walk down the boardwalk, trying to get as far away from that window as possible. With each step, Kelli and Annie regaled me in the story of their day, of lounging by the pool and going to the beach and laughing all afternoon long while I sat in the window waiting for them.

Somehow they seemed older. They’d been in summer meetings for the high school field hockey team, and they seemed to have their own language. They would speak an entire sentence from start to finish and then use the word “psych.” This was short for “psych out,” and it was an atomic bomb in 1990s teenage lingo, blasting all meaning in the previous sentence and leaving anyone who believed a word of it searching for signs that it ever existed. For instance, they might say, “Oh, we should go into that arcade,” and I might say, “That sounds like fun!” at which point they’d say, “Psych!”

They were friendly as always, but they talked to each other more than to me as we walked on, past all the places I loved as a kid. Somewhere around the amusement park, they started talking about the two boys they’d met at summer camp, two boys who were by now very serious boyfriends.

Oh.

My throat felt like I’d swallowed a Skee-Ball. All around me the air filled with the sound of kids honking those duck-murdering horns. I tried to be cool about it. I told them it was great news. As I tried to process the latest in a long line of women I’d never kiss, we reached the very end of the boardwalk, which is basically an ode to the island’s past as a fishing town and home of a life-saving station. Here, in a glass case, is a giant, mounted tiger shark.

PAUL ROGERS

Finally! Something I knew something about. This, my father had taught me years earlier, was the largest fish ever caught in the state of Maryland. More than 1,200 pounds! There’s no way they couldn’t be impressed by this, right? I did my best impression of my dad, rattling off facts about how it was caught in 1983, how sharks like this fight for hours, and how we were looking at the royalty of Maryland fish.

The girls called it interesting and kept walking.

“Yeah, psych,” I muttered under my breath.

Here’s where I could blame my father for all of my past and future breakups with women, but I remember this as one of the few moments in my teenage existence that I realized he had a point. I’d spent the entire day moving about as much as that dead shark, waiting and worrying myself with life’s big questions—while at the beach. Meanwhile, Annie and Kelli had a fine time enjoying where they were—at the beach.

Related: 9 Tips to Stop Worrying

Within an hour or so we were back at the spot in the boardwalk between Paul Revere Smorgasbord and Sand Jesus. Annie and Kelli went back to their place and I went up the rickety elevator and opened the door to my family’s small room, which, all things considered, wasn’t half bad. My parents and brother were showered and ready. We went out for a big crab feast and my father offered me up for marriage to the waitress and I turned red and everybody laughed.

The next day, I rode waves all morning with Kenny. After that we went to the waterpark and slid down the big slide that went straight down like 12 times, and after that we went to the roller coaster and went upside down six times over and over again.

Then we got Thrasher’s fries and doused them in vinegar and salt. They tasted just like we remembered.

***

That fall, we grew up fast. I got assigned a red locker in the bomb shelter section of our high school, a holdover from the Cold War. That November, a bright, smiling 15-year-old sophomore girl died from “huffing,” or inhaling propane from a gas grill hose to get high. The Washington Post ran an in-depth story on how our school had become ground zero for kids seeking quick highs.

Reality Bites, the Winona Ryder-led movie that still serves as Hollywood’s definition of Generation X’s personality, came out the following February, but I didn’t watch it until years later. Two months after that, Kurt Cobain committed suicide. The older kids at school wore all black that week.

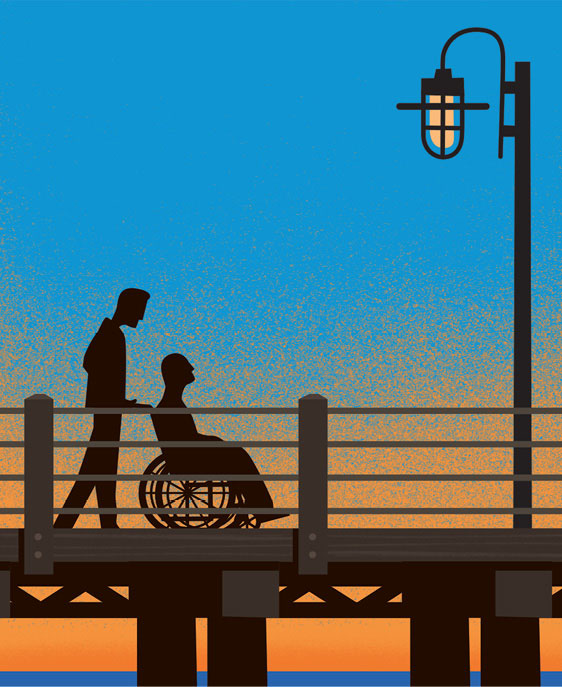

Pages turned more quickly after that, and in the spring of 2015, my parents moved to the coast of North Carolina, into a home they had built with wide doors and railings for my father, who needs a wheelchair to get around now. We’ve all been whipped in different ways since 1993—he’s had strokes and I’ve been divorced—but we get along.

I visited my parents out there on a Saturday this past August. That afternoon, we went to Wilmington, North Carolina, and set out for the Riverwalk, a less-traveled wooden walkway that runs along the Cape Fear River. I pushed Dad’s wheelchair over the boards. We ate a half-decent meal. I pushed him to the bathroom a few times and helped him keep his balance while he went. Then we went back to their house and I searched through old photos, looking for shots from those early years at Ocean City.

PAUL ROGERS

Of all the trips we took, from the years when I was a boy to the last trip in 2014 for Mom’s 63rd birthday, that 1993 trip produced the least amount of photographic evidence. But one picture stands out. In it, Dad, Kenny and I are walking north along the boardwalk. Judging from the relative size of the Ferris wheel and water slides in the background, it couldn’t have been far from the Plim Plaza and Paul Revere and Sand Jesus. Kenny’s in the background of the photo, fiddling with something in his hands. My father’s just ahead of Kenny, in between his two boys, and he’s walking.

If I had one wish now it would be to go back in time and tell that awkward boy he had every reason in the world to smile.

The shot catches him with one foot stepping in front of the other. It startled me, staring at that photo. It’s been a few years since we’ve seen Dad walk without the aid of a walker or a chair. I’m in the foreground of the picture, and if I had one wish now it would be to go back in time and tell that awkward boy he had every reason in the world to smile.

Related: 14 Loving Quotes About Family

This article originally appeared in the December 2016 issue of SUCCESS magazine.